Jonathan Dodd‘s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

Last week I left myself in a Motorway Services over ten years ago, searching for Walnut Whips after my first day working at Honda in Swindon. While I was there I coughed. This wasn’t a full-fledged smoker’s cough, or the hacking of a sore throat, or even the death rattle at the end of some awful illness, it was a somewhat polite “AH-HA!” into a raised hand, like a slightly emphasised clearing of the throat.

When I coughed I felt something give, somewhere deep inside, and my Internal Health Monitor Voice sent me a message. The message was this – “There is something very wrong with your left lung.” It’s a very reassuring thing to have a confident and calm voice utter things like that in your head, even when the news isn’t welcome. I believed her, and of course I ignored it. What was I going to do about a dodgy lung in a Motorway Services?

We think our mouths do the breathing

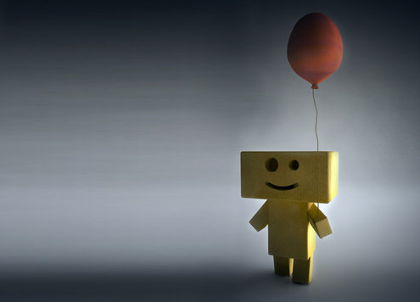

By the time I got home I was having trouble breathing. This is where your cardboard box and balloon come in. The interesting thing about breathing is that we imagine it all wrong. We think our mouths do the breathing, but all the action takes place down there in the diaphragm, which we’ve never even seen.

Imagine instead a sealed cardboard box with its base replaced by a rubber sheet, and a balloon hanging down inside a small hole in the top. If you pinch and pull the rubber sheet, air gets pulled in through the hole in the top and the balloon expands. When you let go of the rubber sheet the air gets pushed out of the balloon, which shrinks back to its original size. That’s how breathing works.

I did have an interesting 15 minutes

So what happened to me was a ‘Spontaneous Pneumothorax’. Like if the balloon in the box develops a small leak and air escapes into the box, that air can’t be pushed out again, and gradually more and more air goes into the space between the box and the balloon. Without intervention, every breath you take increases the pressure inside your ribs, and you suffocate and it stops your heart beating. And it hurts.

Of course, I didn’t know anything about this at the time, and if I hadn’t survived this column would be extraordinary indeed. I did have an interesting 15 minutes after I called the ambulance. My Internal Health Monitor Voice kept calmly and authoritatively telling me I was going to die unless someone performed some miracle, and I was able to review my whole life and say goodbye to everything and everyone in my mind. I was pleased to find that I was calm and everything I believed remained intact.

After I passed out they stabbed me

Medical people perform miracles all the time, and they don’t even realise. They knew what to do. After I passed out they stabbed me, which relieved the pressure, and I ended up in Guy’s Hospital where they not only fixed my lung, but they stopped it ever happening again by sticking the outside skin of my lung to the inside wall of my ribs. Like expanding the balloon until it becomes the lining of the box, with no gaps between.

I won’t have anything bad said about medical people, and everything that’s happened since has been a blessing and a bit like that wonderful film ‘A Matter of Life and Death’. It’s not borrowed time, and it’s not stolen time, it’s more a matter of bonus time, to be used as fully as I can. I think I’m doing that.

Nobody knows why

When I was in hospital a friend of mine sent an email to my entire contact list about being temporally incapacitated, and I went off to Guy’s for my operation. This pneumothorax thing is very rare, and it usually happens to young men around 25. Nobody knows why. And I was twice that age, so the odds were even greater. I’ve only met one other person who had one.

On the day they were going to discharge me a familiar face appeared in my ward. It was someone I had worked with years before. He said he had received my email, and had felt impelled to come and see me. We had been close colleagues rather than friends, so I was surprised and pleased that he came to see me.

Chattering on about scuba diving

We were talking about the thing, and I was saying that before the operation I asked the surgeon whether I’d be able to go scuba diving ever again, and that I wanted that to be a factor in his treatment decision-making. I noticed the strange look on his face, and I asked him what the matter was.

He told me that when he was about 25 he had a similar thing happen one Christmas. It wasn’t as bad as mine, and it managed to heal itself in time, but he said he hurt so much and it frightened him so much that he never took any risks again. I felt a little chastened, chattering on about scuba diving like that, and I felt very sorry for him.

I never even got paid

He insisted on driving me home all the way to Newbury and I lost his address soon after and I never saw him again. I wish I could, because I’d like to talk more with him. Once I realised I was going to survive I just took it for granted that I would go on, and I hadn’t realised that others might react in a different way. I haven’t got an answer to that.

When I didn’t reappear at Honda the next day, they gave my contract to someone else, and I never even got paid. But I did go scuba diving again.

And here I still am, still chattering on, and very pleasant it is.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: Jon Rubinunder CC BY 2.0

Image: Relderson under CC BY 2.0

Image: jvk under CC BY 2.0

Image: Snapper 31 under CC BY 2.0

Image: Google Cultural Institute under CC BY 2.0

Image: Liz Henry under CC BY 2.0