Jonathan Dodd‘s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I’ve been trying to make myself a definition of ‘Civilisation’. It’s a word I use a lot, and like almost all the words we use, I haven’t learned it from a dictionary or encyclopaedia. The normal way to ‘learn’ what a word means is to build up a cloud of meanings and allusions and quotes and ideas picked up over a lifetime. So I’m very familiar with the concept of Civilisation, and I can talk about it for ages (but then what is there that I can’t talk about for ages?), but of course that’s not good enough for me, so now I want to be able to define it.

The reason for this pressing need is obvious, at least to me, because I think that we used to have some sort of civilisation, but I have a bad feeling we’re losing it. I work as a tester in IT, and it suits me very well, partly because I like things to be clear. The principle of testing is very simple, it’s all about expected results. You can’t just test stuff, you need to know what it’s supposed to do first, otherwise you won’t know whether it’s behaving as it’s supposed to or not. And I’m not entirely certain what this civilisation thing is supposed to do.

Throwing all the parts over a cliff

I hold this truth to be self-evident, but it’s amazing how many people, even in IT, think all that’s a waste of time. To me that’s like getting on a train without checking where it’s going, or designing an aeroplane by throwing all the parts over a cliff and hoping you’ll be able to put it together before you hit the ground. It’s completely nonsensical. And it happens all the time.

Wherever I work, the quality of the project and the success of the delivery are always dependent on two things. First, there has to be some sort of requirement and design. The better and more complete these are, the better the chances of success, and the more time saved, because there’s less room for error and ambiguity and bad assumptions. The second factor is even more important, and it’s simply that everyone needs to buy in to the work itself. In other words, the work needs to feel like a common goal. It’s as simple as that. And it’s as rare and valuable as dragon’s eggs.

The Hierarchy of Needs

I have a feeling that my definition of civilisation will have a lot in common with this idea. We tend to think of civilisations in terms of their cultural artefacts; their buildings and works of art and the systems of knowledge and understanding that they create. But these things aren’t the civilisation itself, they’re made possible by the existence of the civilisation. In other words, a civilisation is an environment in which learning and research and progress in many areas of endeavour are encouraged and celebrated.

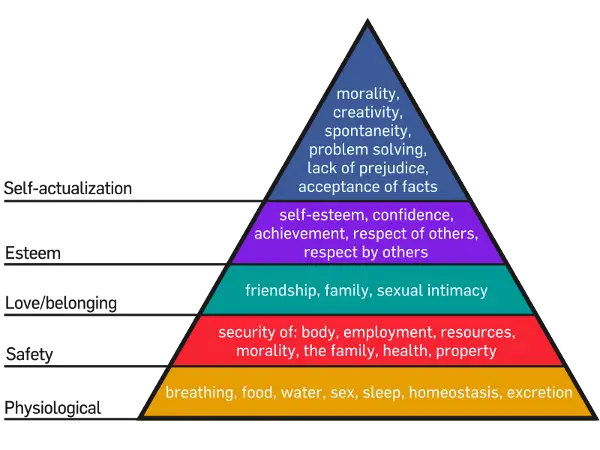

At teacher training college I was taught that certain things must be in place if you’re going to learn anything. You need to feel comfortable and safe and valued, you need to understand that education is an important part of your life, and you need to have an idea of the value of the education you’re about to receive. I’m glad I remembered that. Abraham Maslow. The Hierarchy of Needs. Google it if you like. As far as I can see this is a principle that ought to apply to every citizen in a civilised society. When we talk about ‘social exclusion’, it’s not just words, it’s a principle, and it means something important.

It sometimes took them quite a long time to work it out

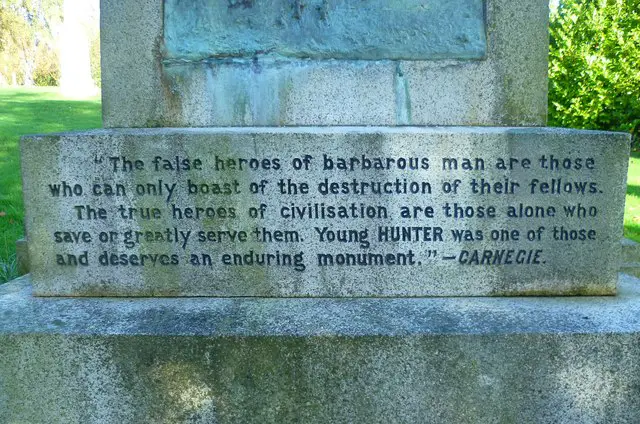

I like the idea of principles. They imply that you’re doing what you do with extra content, for a purpose that is greater than and additional to the simple practicalities. For instance, it’s fashionable to think of the Victorians as being far too smug, but they did understand certain things, even if it sometimes took them quite a long time to work it out. They liked to build their public buildings and their workplaces large and imposing.

This is often seen nowadays as boasting about your power and influence, but I think it’s more than that. It also demonstrates the importance that the builders gave to the purpose of the building. Railway stations, libraries, water pumping stations, churches and government offices were built to last, to become a monument to the purpose and intent of the building. This was partly because it was very early days for governments to be considering the health and well-being of their citizens, and they felt good about it. Even public toilets were built to a style and standard way above what was functionally required. And even today, many of these buildings are loved.

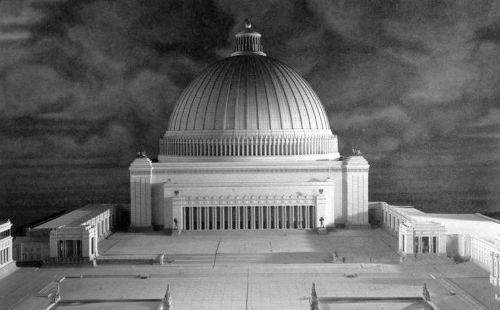

Communities are less important than plumbing

Dictators build large too, to illustrate their power, but nobody loves those buildings that survive their originator, because they have only one purpose, and they weren’t designed with any finer feelings or aspirations in mind. In the same way, the high-rise blocks built after the Second World War have mostly fallen into disrepute and disrepair. I’m not saying that they would never have worked, or that they didn’t work because they were ugly. What the builders forgot was that the slums they replaced contained real communities. Perhaps the planners assumed that communities are less important than plumbing.

So. I’m arguing for civilisation that has a culture with the idea of quality and service at its heart. You need plumbing and communities. I like the idea of people having principles to guide their plans and actions, and some idea of the common good. I like the idea of making society inclusive and welcoming. I like the idea that progress and knowledge are of primary importance, in order to develop everyone’s talents and abilities.

A kind of glue that stuck people together

Many people look to the past, when everything was supposed to be so much better. We cherish the idea that most people went to church, children were generally polite and well-behaved, everyone learned to swim at school, and schools would lend out musical instruments as well as books to their pupils. I’m willing to bet that this really did exist, but only for part of the population. And the downside to this was a terrible conformity and smugness, a fear of anything new and some very unpleasant attitudes towards anyone who was different. I don’t want those things back. I just think that the idea served as a kind of glue that stuck people together, and we haven’t replaced that.

I’m very happy to live in a country where many of the small things are so much better than they were. We celebrate difference and diversity, although not everyone understands how important this is yet. Everyone goes to school, and we have the NHS. Things are safer and better-designed and more available to more people, but I’m not sure we’re happier. As a country we don’t know what we stand for any more. Maybe we never did, maybe we just followed our leaders. Maybe we stopped doing that, or maybe the leaders became less charismatic. I actually don’t know.

A lack of proper outrage

What I’ve been thinking about recently is that there seems to be an appetite for a new barbarianism out there. I feel a little like the citizens of the late Roman Empire must have, with the Goths and Visigoths and Vandals on the horizon. There seems to be a leaking away of resolve and a lack of proper outrage when we hear about the awful things being wrought by a group of people who seem to feel that every precious foundation of civilisation must be torn down and ground into the dirt.

I’m not talking about going to war in a strange country. We’ve done a lot of that lately, and we’ve failed, in fact we’ve probably made it worse. I’m not talking about spending a lot more on defence. I’m talking about making sure that we’ve still got enough of a civilisation to want to defend should it come to that. In the face of barbarism we should be upping our game, becoming excellent in every way, to remind ourselves of why civilisation is worth saving, and to speak with a strong voice against the tide of destruction.

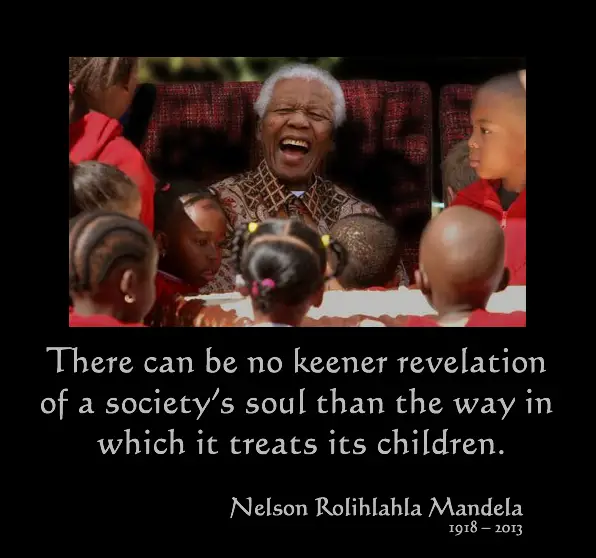

There are many young people in our midst who want to make the world better, and many of them have no hope of doing so. Some of them are going to fight for IS, choosing barbarity cynically clothed in religious words. We must have something better to offer them. Our country should be a place where all sorts of heroes and dreamers can thrive.

That’s my definition of Civilisation.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: kim traynor under CC BY 2.0

Image: wbaiv under CC BY 2.0

Image: FactoryJoe under CC BY 2.0

Image: Christine Matthews under CC BY 2.0

Image: Bundesarchiv Bild by Srittau under CC BY 2.0

Image: trondheim_byarkiv under CC BY 2.0

Image: hinkelstone under CC BY 2.0

Image: Seenowiam under CC BY 2.0