Jonathan Dodd‘s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

Everyone loves a beach. What’s there not to love? You’ve got all sorts of weather, lots of space, fresh air, the sea, some kind of view, at least interesting and sometimes beautiful, and very few people go to the beach to work. Usually the beach is all about holidays and having fun.

That’s how I remember it. I was lucky enough to grow up by the sea, and most of my time during my formative years was either at the beach or close to it. I remember my home sea in all its moods, from dead calm to so furious it seemed to want to rip the shoreline into pieces and rampage through my home town. I walked along it on the promenade or the pebbles or the sand, I threw so many of its stones back in that I was surprised not to change the shape of its beaches.

I once felt the undertow

I used to paddle and swim in and under it, sometimes I could body-surf, although there was hardly any chance to surf properly unless the tide was low and usually only when it was very windy and the red flag was out. I did take notice of the red flag, because I once felt the undertow, sucking at my legs and pulling me out to sea, and that scared me.

I loved to wait until low tide exposed the huge flat expanse of sand, which hardly ever dried out. As soon as I could, I’d be down there digging furiously, trying to dam one of the small streams that made miniature Grand Canyons. The idea was to make a wall across the main stream and then keep digging in a great arc, trying to keep ahead of the rising water before it escaped round the side or breached the wall. I wasn’t interested in nice sandcastles, I wanted to do big things with that sand.

That dull ringing sound which only flint makes

I was lucky that my beach had pebbles above and sand below. I loved the way the pebbles seemed to zone themselves, with great banks of large stones, grading themselves down to fine gravel and finally becoming so tiny that they were almost indistinguishable from the sand itself. I loved the sound the large stones made as you walked on them. They cracked and tinkled like glass, and miniature avalanches I set off made that dull ringing sound which only flint makes, with its rough smooth skin and glassy inside.

I used to hunt for different things whilst walking along. There was always a line where the last high tide had reached, where skeins of seaweed were starting to smell as it dried, and you could find pieces of driftwood and other flotsam. There were lots of crab shells here, and cuttlefish bones, and the remains of fishing nets and great messes of fishing line, sometimes with hooks still attached, so these had to be explored carefully.

How they changed when they dried

I used to look out for flat round shells which would be good for skimming, although I was never as good as my brothers. I looked for stones with holes right through them, or with faces or the shapes of animals. I looked for shells too, although pebble beaches don’t usually have many intact shells, they’re usually mashed up very efficiently by the waves and the stones. There were lots of mussel shells and limpets, and some oyster shells, and sometimes the remains of other more interesting ones.

I looked for sea glass too, waiting for that tell-tale glint of colour as the sun caught it, or a tiny wave exposed it in the water. I was always fascinated by the difference in the colour of things when they were wet and how they changed when they dried.

They would wave their great pincers around wildly

There were lots of living things there too. We didn’t have rock pools where I lived, but there were lots of groynes, built of timber or concrete, sticking out in regular lines to try to stop the beaches being washed completely away by the current and the tides, always rolling and pushing eastwards away from the Atlantic and towards the North Sea, as if the breaching of the land between us and Europe at Dover was a terrible mistake, and Nature was patiently trying to close the gap again.

Under each of these groynes, at low tide, were pools which contained shrimps and tiny fish and sea anemones and crabs, usually under stones or hiding under a layer of sand, with only two small holes visible, emitting a tiny stream of bubbles. I learned how to burrow my thumb and middle finger into the sand and catch the crab by getting hold of the side edges of their shells with these two fingers and lifting them up. They would furiously blow bubbles at me and wave their great pincers around wildly, trying to get hold of whatever it was that held them tight. If you missed and they grabbed you, it hurt like hell.

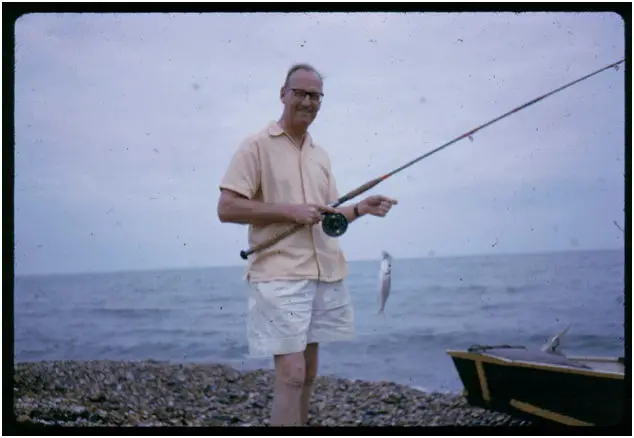

I balked at hitting it on the head with a stone

I was shown all this by my father when we were out together, and I carried this on for myself. He loved to fish, and when he wasn’t working he would take his long rod down to the beach and cast it out far into the water, hoping to catch bass. I never became a fisherman though. I tried it a few times, and once caught some fish, only one of which was good enough to keep. I balked at hitting it on the head with a stone, and decided it wasn’t for me.

But this didn’t make me a vegetarian. That came decades later. The thing that I loved to do with my father was to catch shrimp. He was good at making shrimp nets. These were basic but very effective. They were made with a long handle like a broomstick, with a piece of wood attached across the lower end, like an inverted ‘T’. Then he attached a half-circle of bamboo to the handle and the ends of the bar, and sewed a net bag behind.

We would shell them and eat them

He had a large one and I had a smaller one. We would go out at the right tide and walk along in the shallow water, pushing these nets in front of us, disturbing the top layer of sand, and sweeping the prawns into the nets. Once we had enough, we would shake them all into a bucket and go home.

My mother would boil up a huge saucepan of water, and we would tip our bucket into it. I used to watch the shrimps turn from being practically transparent to a delicate pink, and when they had cooled down we would shell them and eat them. They tasted delicious.

The most amazing contradictions

Once I asked my father if I could keep some. He warned me that they would die if they were away from the salt water, so I collected a few in a bucket of sea water and put them in the shed for the night. In the morning they were all dead, and I felt terrible about that.

Now, I think about all the shrimp that I watched casually being thrown into boiling water and I can’t understand why I felt – and (weirdly) still feel – terrible about those few shrimp dead in a bucket. But that’s just how we humans are. We can live quite happily with the most amazing contradictions.

The other day I saw Pluto, so I picked it up and took it home. It’s quite amazing what you can find on a beach.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: Christine Matthews under CC BY 2.0

Image: Alan Slater under CC BY 2.0

Image: Simon Carey under CC BY 2.0

Image: antonymayfield under CC BY 2.0

Image: Simon Carey under CC BY 2.0

Image: © Jonathan Dodd

Image: Benjwong under CC BY 2.0

Image: © Jonathan Dodd