Jonathan Dodd‘s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

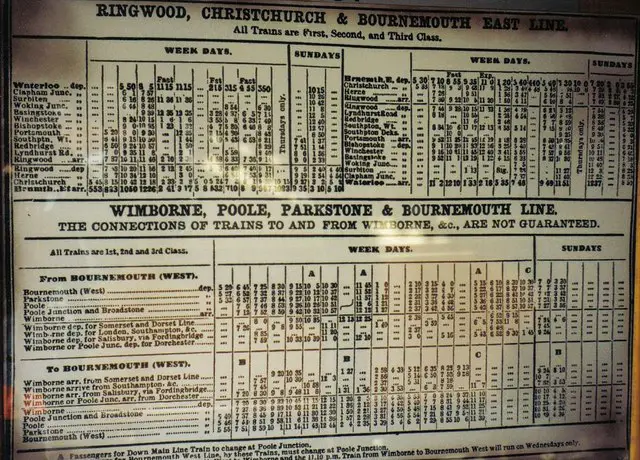

My mother was never able to read train timetables. She used to say it was because she left school at 14, and she used to think she was stupid, even though she absolutely wasn’t. When I was at school she used to ask me to read timetables or any sort of chart for her, and I was proud to be able to show off. I thought, in that simple way children do, that she was teaching me. It was only many years later that I realised how much practical help I was actually giving her.

When I found myself in Teacher Training College learning how to be a Primary School teacher, I was told over and over that there’s no such thing as dyslexia. I never believed anything my lecturers told me, luckily, because much of the time they were wrong.

Without understanding the irony

Example: They used to arrive for a lecture and recite monotonously their notes, which were invariably yellowing with age and falling apart at the folds.

Example: Taking two hours to tell a room of 300 people that you can’t hold the attention of more than eight people for more than ten minutes. Without understanding the irony.

Mind you, most of my fellow students didn’t get it either. This was well beyond the end of the Sixties, and the college had only just decided to allow the female students to wear trousers. It all reminds me of an old joke that was going the rounds at the time. You’ll have to adjust the institutions for whatever applies nowadays. It goes like this.

Three hundred pens

Monday morning, a University lecturer gets up, goes to the lecture hall, gets her notes out, clears her throat, looks up, and says “Good morning”. There’s nobody there.

Monday morning, a Polytechnic lecturer gets up, goes to the lecture hall, gets her notes out, clears her throat, looks up, and says “Good morning”. The room’s half-full. One person shouts out – “Is it?”

Monday morning, a College of Ed lecturer gets up, goes to the lecture hall, gets her notes out, clears her throat, looks up, and says “Good morning”. And three hundred pens write down the words – “Good morning” in their notebooks.

Anyway, I survived College of Ed and taught for a while, and then I had children of my own. Both of them had a version of dyslexia, and both of them had trouble at school with teachers who kept saying they were bright but lazy, spoilt and unwilling to concentrate. We were at our wits’ end until someone told us about a small clinic. So we booked them in, and the problem was diagnosed and fixed. Like the best magic, it was wonderful and looked so simple.

Happier in a different learning environment

Then we had to change their school, because the previously-negligent teachers refused to acknowledge that anything had been amiss. Or had been rectified. They all must have gone to the same College of Ed I attended, because, rather than learning about the condition, they continued to deny its existence. They suggested that our children might be happier in a different learning environment. We couldn’t help but agree. The irony was lost on them as well.

It was around then that I began to remember my mother and her inability to read timetables. Of course, when she was a girl, destined to leave school and work in a post office at 14, there wasn’t even a condition or a name that you could deny. Whatever you might think about the world today compared with whichever rose-tinted version of the past you favour, it cannot be denied that there has been a huge explosion of knowledge. No matter that some people think the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction, nobody denies the existence of dyslexia today. In fact, there are numerous varieties now.

Like a knowledge landslip

I know this because I have my own difficulty, although in a milder form. I find myself incapable of remembering what happens to clocks twice a year, and currency conversion defeats me. I can have it explained to me, and I get it, for about five minutes, but then it just sort of slides away, like a knowledge landslip. Sometimes also I miss completely the point of something that is said to me. Afterwards I’m mortified, and I’m ashamed to say that I sometimes bluff it out, even though it always makes things worse. The difference between my mother and me is that people have always told me that I’m intelligent. This, along with a healthy dose of inflated self-respect, I accept as my due, because I know I’m intelligent. I do also know that I can be very stupid sometimes, and there are things I’m never going to understand, but generally I feel I’m up to any task that life might throw at me.

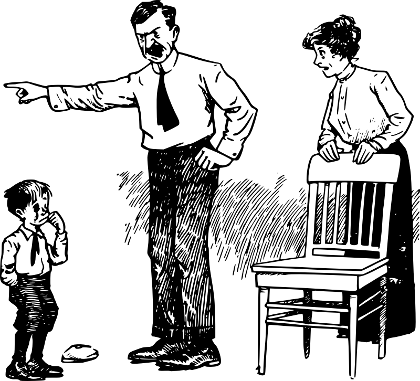

One thing I was careful about with my children is that I never told them they were stupid. I went out of my way to say the opposite. On the one hand, you have – “You’re stupid!” On the other, you have “You’re not stupid, you’ve done a stupid thing!” Which would you prefer to hear shouted at you? Apart from the difference in words, the sense is quite different. The stupidity isn’t something inside the person any more, it’s now something the person has done. And if it’s a thing done, it doesn’t have to be done again. It suggests that they don’t have to do it again, if they think about it.

Out it came in an uncontrolled moment

In the same way, one of my mother’s favourite things to say was this – “I may look stupid, but I’m not!” Obviously, to a child, the immediate answer, which must never be spoken aloud, is – “Oh yes you are!” I had a horrible sinking feeling that I would start using this phrase, heard a million times throughout my own childhood, and sure enough, out it came in an uncontrolled moment. I felt awful. My brainwave was to change the words around. So I used to shout this instead – “I may be stupid, but I don’t look it!”

This had many beneficial effects. First, I was never actually repeating what my mother had shouted at me. Secondly, I wasn’t insulting my children. Third, I wasn’t being pompous. Fourth, the sound of my voice still had the desired effect. Fifth, and most important, was that it never ceased to make me laugh, which made me calm down and everything became easier very quickly. And sixth, I knew one day that one of my children would actually listen to the words rather than react to the tone. The day it did was glorious, like the longest shaggy dog story punchline ever. And I could still use it for years afterwards, because everybody laughed. Every time.

Everyone who’s clever has things they just can’t do

OK, it’s a fine story. But I know many many adults who feel deep down inside that they’re not clever, possibly they’re stupid, that they can’t succeed, that they’re bound to fail, that they don’t deserve good things. They may never acknowledge this, they may harbour hidden anger and disappointment, they may be unable to lead a full emotional life, and it’s all completely unnecessary. Because everyone who’s clever has things they just can’t do, and everyone who’s supposed to be stupid has things they do or could do wonderfully well.

I think it’s vital to tell everyone from as early an age as possible that they’re clever, and to praise them for everything they learn, every good or kind deed they do, and to have the expectation that they’ll prove and improve their intelligence and skill in every situation. This should be a lifelong investment for everyone, and it should never stop. You still need to tell people off or punish them for doing the wrong thing, but nobody should ever be told that they are stupid, or that they are worthless, or that they are ugly, because each of these is a lie.

I don’t think anyone should spend their lives lying to people, especially young and impressionable children. Do you? And nobody should spend their life being lied to by everybody else.

What’s the sense in that?

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: Chris Downer under CC BY 2.0

Image: Xbxg32000 under CC BY 2.0

Image: Paul under CC BY 2.0

Image: Willard5 under CC BY 2.0

Image: ChipmunkRaccoon2 under CC BY 2.0

Image: j4p4n under CC BY 2.0

Image: tsou3llc under CC BY 2.0

Image: D. Sharon Pruitt under CC BY 2.0