Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

Back when I was at school, I felt a strong attraction towards arts subjects. I think this was caused by two things. Firstly, I’m the kind of person who loves words and pictures and I love the sort of fluid thinking you can make ideas into without having to fit everything into frameworks. This is not laziness, it’s a sort of variation of Romanticism. At least that’s my excuse.

Secondly, I had a completely different experience in school during science lessons. There was a lot of sitting and listening to information that didn’t seem very interesting, at least to me, and a lot of having to learn and remember things, like the Periodic Table, without being given much idea of what the purpose was.

I was bored

I’m not making excuses for myself, and I’m not necessarily criticising my science teachers, but I can’t lie about it, I was bored. And perhaps I was unlucky, because all my science subjects were like this. If one of these teachers had stood out as being interested and interesting, I might have ended up with a different opinion.

There were some moments that stood out. Like growing blue crystals. And there was that description of an atom, in which our laboratory classroom was compared to the nucleus, with the nearest electron whizzing round as far away as Paris. I had been to Paris. I could conceive of this vast space. It thrilled me, but in a strictly literary way.

Mostly because it was cool

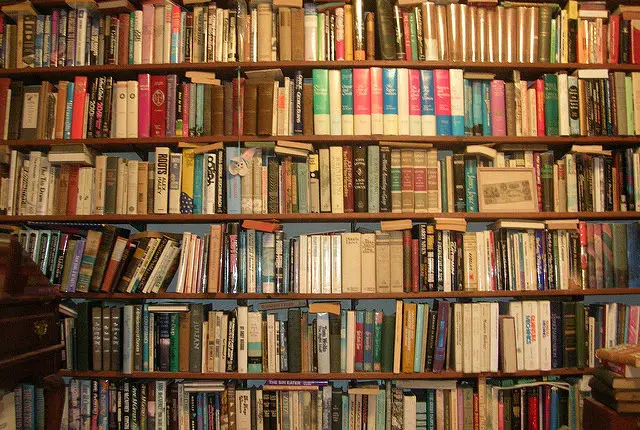

English was my favourite subject. From the moment I could open a book I was hooked. Being expected to read various books and then talk or write about them came as second-nature to me. I loved French too, partly because I had a good accent, partly because it opened up a whole new way of looking at the world. But mostly because it was cool.

I knew people who loathed English, and even some who found Maths terribly exciting, or spent long hours perfecting skills in the lab, or finishing a sculpture, or pounding round a running track, or learning how to kick a ball accurately. This is because everyone is different, and the reasons we have for doing one thing rather than another are as secret and mysterious as ever they were.

Adults make no sense at all

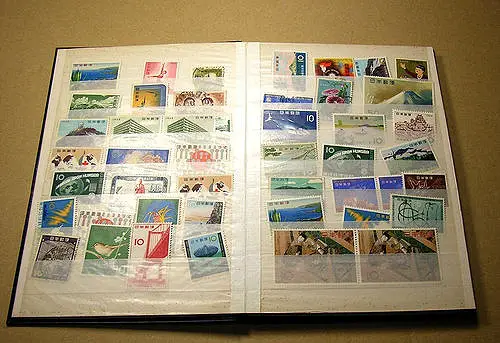

There were others I knew who had immensely exciting out-of-school lives too. I had a friend who built amplifiers, and another who loved to climb, until he was badly injured in a fall. I knew people who went fishing, or collected stamps, or practised the guitar endlessly. Some of these went on to make careers out of these hobbies. And I knew some people who didn’t seem to connect particularly to anything.

I never knew what I wanted to do. It seems to me to be a ridiculous habit of most adults, when confronted by a small mostly-unformed person, to lean over them and ask them what they want to do when they grow up. How could any child know what they’re going to grow into and what slot they’ll fit into or create in that elusive adult world? But then, as any child knows instinctively, adults make no sense at all.

I parked my critical self in the foyer

The thing I liked best was reading, and then watching films. But I didn’t know how to convert that into a job, partly because I stopped enjoying having to study and criticise books, because thinking about the book itself started to spoil the pleasure of reading them. I once had a mildly-enjoyable horror film spoilt totally by a couple in the row behind me talking incessantly about wrong camera angles and bad direction and continuity mishaps.

I found a way of preventing this, by splitting myself into two. First, there was the fanboy, throwing himself into the world of the film or the book, enjoying the ride and the imaginative leap. Then, and only afterwards, I allowed myself to think about the thing as a work of art, and decide what was good and what was bad, interesting or dull. I parked my critical self in the foyer, with strict instructions to stay still and quiet, until his turn came to speak.

Same story, different perspective

This has worked rather well for me ever since. Occasionally I write reviews, and the skills I learned allow me to experience everything fully, then recall it all afterwards so I can put my thoughts into print. I’ve even managed a way to stop that old argument about ‘Is the book better than the film, or vice versa?’

I imagine a story as a thing in itself, and I put it in the middle of a circle, like the centre of a clock face. When I read a book, I find myself approaching the story from the ‘Book’ direction, and entering it via the ‘Book’ gate. Then, if it becomes a film, I go into it from the ‘Film’ side instead, and inevitably I’ll experience the story in a different way. It’s a bit like touring Osborne House one year, and going to the Needles the year after. Same island, different perspective.

Without having much idea what they look like

That works well for me. I’m also blessed with a mind that loves ideas but doesn’t paint pictures much. So I love Elizabeth Bennett and Owen Meany and Lyra Belacqua without having much idea what they look like. Then when I see them on-screen, I don’t find their appearance clashing with an image I’ve already created. And, miraculously, if I see other actors playing the same parts, I still don’t have a problem with that. It’s a different version.

So I’ve come to the conclusion that we make up our own lives, using the tools we’re born with. If we’re lucky, we get to enjoy some of the things we instinctively like doing anyway. If we’re unlucky, or maybe not that engaged, we end up doing something that keeps us ticking over. If we’re very unlucky, we may find ourselves with little or no choice, but there’s always a little leeway around the edges.

Music to the minds of uncomprehending adults

I guess we’re very lucky if we home in on something we want to do at a very early age. Much unnecessary studying and anguish can be avoided this way, and those annoying adults become completely irrelevant because they get a straight answer. ‘I want to be a Train Driver!’ ‘I want to be a Dancer!’ ‘I want to become a hedge-fund manager!’ These ideas are music to the minds of uncomprehending adults.

I knew someone who became destined to be a doctor. He worked hard at school, took the right courses, got the right results, and worked through six years of medical school. Until he had to meet the public and deal with real medicine on the A&E front line. That was when he finally admitted that he couldn’t stand the sight of blood.

What do you do if you can’t do the thing you really want to do?

I think he was so far down the road that he couldn’t bear the thought of all that disappointment and embarrassment. Luckily, he was able to make a very good career for himself in an area related to medicine but not needing to practise it. So sometimes knowing what you want to do doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll succeed, and there’s an element of all eggs in one basket there too. What do you do if you can’t do the thing you really want to do?

Since I never knew what I wanted to do anyway, I don’t have those regrets, and I’m very grateful I haven’t. I rather wish I could harness some of that book-reading into something that paid well, and it would be rather good to write one of those novels or films that I admire so much.

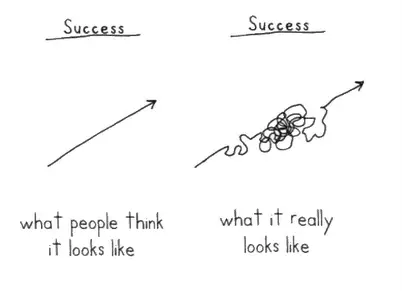

Success can be measured in so many ways

But the one thing I do know is that there’s no such thing as ‘too late’. Everything that came before is just part of the preparation for where you are now, and where you can be tomorrow, if you want it enough and if you’re ready when the opportunity arrives. I wish you luck, and every success.

Of course, success can be measured in so many ways. You can sing well, without needing to be Rihanna, you can be happy, without being rich. You can be a great railway modeller, or stamp collector, or angler, or you can be proud of being a parent who brought good people into the world. You can use your own imagination to define your own definition of success. And you can celebrate the success of all the people you know or don’t know without having to be jealous or judgemental.

And now I must get on with that novel. The Great British one.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: benuski under CC BY 2.0

Image: Queensland State Archives under CC BY 2.0

Image: bgsulib67 under CC BY 2.0

Image: itchys under CC BY 2.0

Image: Rwendland under CC BY 2.0

Image: M J Richardson under CC BY 2.0

Image: Public Domain

Image: Walter Baxter

Image: Public Domain

Image: topgold under CC BY 2.0