Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I used to be confused. Now I really can’t tell whether I’m confused or not. Confusion seems to be a more or less constant state that most of us are in most of the time, whether we know it or not. And, like it or not, most of us don’t even know whether we’re confused about anything or not, until we have to make a decision about something.

Confused? You won’t be after this week’s column. Or maybe you will, or maybe you’ll become less confused, or more aware of the extent of your confusion. My intention is to say a few things that might make the whole confusion business a little less confusing. I hope that’s what happens.

That is what I call ‘a good problem’

OK. First of all, we have to decide what confusion really means. When I googled it, the definition I liked most was this. ‘The state of being bewildered or unclear in one’s mind about something’. We need to decide whether confusion is internal, as in – ‘I don’t understand what’s going on’, or external, as in – ‘I can see that there’s confusion going on here’.

I would suggest that in the second example, you’re absolutely not confused, because you’re seeing and thinking clearly. Whether you’re going to be able to do anything about this external confusion is a completely different problem. You might be able to turn your internal clarity of thought to trying to understand the causes of the confusion, and decide whether you’re going to be able to do anything about it. That is what I call ‘a good problem’.

The trouble with confusion really, is that we don’t like it

So when you notice a certain amount of confusion, it’s a good thing to take a look, with the aim of deciding whether the confusion is yours or not. Of course, it might be both, but if you can decide this, you are in a good position to separate your own confusion from what’s going on outside you, which in turn gives you the ability to think clearly about it.

The trouble with confusion really, is that we don’t like it. We’re very simple animals mostly. We like things to be comfortable, and we like them to stay comfortable. Some of us are lucky, and this is the state in which we exist. Many of us are comfortable, but we fear that this comfort may be taken from us. And there are many who have no comfort, or no expectation of it.

We do notice at least a frisson of fear

As a species there are many things that drive us on, and I think the desire for comfort, which equates to the desire for safety, is rather important. Some of us take ourselves out of the race because we grab the first thing that offers us a little comfort and stick with it for dear life. Others keep on going, looking for the Golden Comfort, which promises complete protection from anything that could threaten the lifestyle we strive for. These people use the word ‘security’ a lot.

We do notice at least a frisson of fear whenever we stray from our ‘comfort zones’. Some of us like that a bit or a lot. Some of us hate that feeling, and our lives are dominated by the avoidance of that fear. Think ‘Rollercoaster’, and your reaction explains this idea better than anything I can write. And confusion feels a lot like fear.

Avoiding a falling building or waiting to meet one of our heroes

We’re a successful species, because we developed the ability to recognize danger, and we became good at dealing with it. Most species are either predator or prey, so it’s all about running away or being clever and catching our food. We have both in us, but we have the same mechanism for either activity.

The surge of adrenalin that courses through our bodies is designed to get us ready for ‘fight or flight’. It shifts our blood flow to our limbs, speeds up our breathing and puts all our senses on high alert. It’s a brilliant system, but it works in exactly the same way whether we’re avoiding a falling building or waiting to meet one of our heroes or about to go on stage.

The actual somatic activity feels the same

In other words, you can be excited or anxious or afraid, but the actual somatic activity feels the same. We need to remember why we wanted to be ready, otherwise we’re going to confuse anticipation or excitement with fear. One thing we can do about this confusion is to remember what was going on in our minds before we felt that fluttery tummy or our legs went wobbly. It can just as well be a good thing or a bad thing. It means that we’re ready for it, whatever it is.

Now that we can look to see whether there’s confusion inside us or not, we can look at the forms that take and some of the reasons for it. Confusion is always unmistakable, but there are lots of types. There’s the sudden lost feeling confusion. We can feel as if all the things we thought were fixed have disappeared, like waking up because we’ve dreamed we fell out of bed.

Not everything has been thrown up in the air

Life can shock us with events or realizations that shake our foundations. We feel lost and confused. Luckily these moments are rare, and they always resolve themselves in time. It turns out that most of the things we knew are still functioning perfectly well, and it’s only a small percentage that’s changed. Obviously an important percentage.

We become less confused by doing ordinary things in the same old way and comforting ourselves that not everything has been thrown up in the air. And gradually we become aware of the actual extent of the damage and as it becomes familiar we repair our internal world. This always happens, so it’s all right. The confusion is a natural temporary result of the bad thing, and it always goes away.

There is no shame in this

We get confused when confronted with things about which we know very little, or because we just don’t have the capacity to remember what to do. We all have these blank spots. I can never work out currency differences, and I still get very confused by the clocks changing twice a year.

The first thing to say is that there is no shame in this, and usually it isn’t about important things, so there’s no need to worry about them. Just accept it, and there’s always someone who will help, or explain patiently. My mother. bless her, could never work out how to set the timer of her video recorder. Every visit was taken up with me explaining how to do it, and writing it down, and her writing it down, with both of us knowing full well that as soon as I was out of the door everything, including the pieces of paper, would fly away.

All the experts in everything got everything completely wrong

Sometimes there are things too big to understand. We probably don’t know enough to be able to make decisions about them. Often nobody understands them, and various ‘experts’ make it worse by predicting what’s going to happen. We listen to them because we’re confused, and we think they’re giving us the facts, but they’re just soothing our ruffled feathers. Anything they’re actually saying should be taken with a pinch of salt. Witness the whole pre-Brexit fiasco, where all the experts in everything got everything completely wrong.

As above, some people love moments like that, and others find them profoundly frightening. And they’re a perfect example of every type of confusion that there is, and that we might experience. But the thing to remember is that nothing happened as they predicted, and nothing was as bad as they tried to tell us it would be.

It’s called Intelligent Confusion, rather than the other kind

Here we all are, getting on with everything as usual, and things are changing slowly, just as they always have changed, and as they always will change. And it’s all right. SN – Situation Normal. You can add the AFU if that’s the way you like to think about it all. We’re all confused about things and we always will be, but we should take a little effort to define our confusion, or at least to find a way to inspect it. Here’s my tip, which always works for me. It’s called Intelligent Confusion, rather than the other kind.

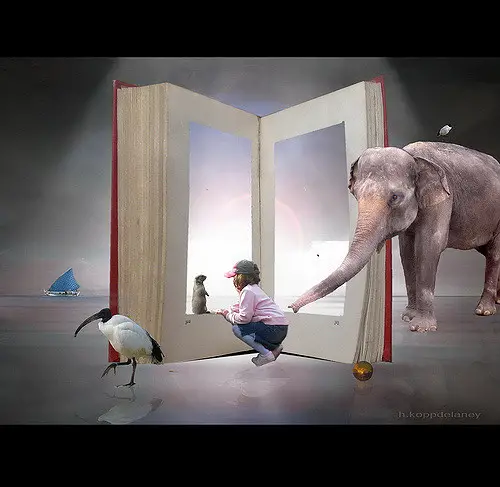

When I’m in a state of confusion about something, be it large or small, the thing I always do is to become still, in body or mind, depending on the circumstances, and actually look at the thing that’s confusing me. The more I look, the more confused and puzzled I seem to become, but sooner or later I notice something, and I ask myself the most intelligent question I can about that bit.

That gives me my anchor

There’s no need to wonder why that question should come first. There’s no need even for it to be answered. But it becomes the focus of my gaze when I’m thinking about the thing that’s confusing me. And because I thought of the question, my view becomes the centre of my questions about it, and that gives me my anchor.

For instance, when I think of Trump now, I find myself trying to make a picture of the mind of someone who actually thinks that he would be worth voting for. It’s a fascinating and somewhat scary process, and I’m very glad to see that it’s someone I could never be. Now I’ve stopped worrying about being confused, and I’m worrying a lot less about him being elected.

Now that’s comforting, and I’m not at all confused about that.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: design_inspiration under CC BY 2.0

Image: Andrew R Tester under CC BY 2.0

Image: Iain Thompson under CC BY 2.0

Image: tedmurphy under CC BY 2.0

Image: public domain

Image: Peretz Partensky under CC BY 2.0

Image: mvdsande under CC BY 2.0

Image: Hermann under CC BY 2.0

Image: dullhunk under CC BY 2.0

Image: h-k-d under CC BY 2.0

Image: perspective under CC BY 2.0