Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I’m sorry. I’m sorry, I’m sorry. If ever there was a phrase in the English language that summed up the English psyche, this is it. I’m sorry to say that this sorry phrase just doesn’t do it for me, and I think it should be expunged from the nation’s consciousness forthwith.

The thing is that this word doesn’t really mean anything. If we say we’re sorry, all that means is that we’re saying we think we ought to feel that we shouldn’t have done the thing we did, or vice versa, and we make appropriate faces. The person we say sorry to is supposed to forgive us, and that’s that, all over.

The hierarchy of badness

I remember so many instances of people saying they’re sorry over the years and thinking they got away with it. I’m sure I did that myself, of course. But only in my younger days, before I became older, and wiser, and more sneaky. Of course, I would claim not to be sneaky at all, but if I was very good at it, how would you know? And a lot depends on what I might or might not be sorry for. It’s part of the hierarchy of badness.

The third best kind of badness is where you have to apologise but the victim is so embarrassed that they tell you it’s all right even though it isn’t. but it’s too late then, so you get away with it. The second-best kind of badness is where they blame someone as long as it’s not you, but by far the best is where you get to do things and nobody thinks there should be anyone to blame. If I were in the sorry-avoiding business I would regard that as a triumph.

The worm that hasn’t turned yet

A very good friend once told me that I didn’t have any bad characters in my stories. They said I just couldn’t get into their heads. I think I agree with her, except I’d rather say that the thought of getting into the head of someone unpleasant rather freaks me out. I know writers who love their villains, and there wouldn’t be any detective murder stories or thrillers without them. I did try it once, but I felt the effect was just plain creepy and not at all realistic. Perhaps I’m not cut out for that sort of story.

I have no idea what makes a bad person (or a person bad), or what happens inside their heads. I suppose I headed myself towards the light and reasonableness too single-mindedly, or I simply have some circuits missing up there in the overgrown undergrowth of my brain. Or perhaps it’s all there, festering away, just waiting for the opportunity or the permission to be unleashed. I might be the worm that hasn’t turned yet.

It was rather thrilling at the time

Who can tell? I certainly can’t. I do remember a childish enthusiasm for all things torture- and death-related. I read stories from Greek Mythology, and vivid retellings of scenes from the Roman Games, and I remember having earnest discussions with equally inexperienced boys about the relative effectiveness of certain tortures we had heard about. I remember it was rather thrilling at the time.

Nowadays we’re all much more knowledgeable, and we see things regularly that were unthinkable in the days when my parents brought me up. I have no idea whether this makes us better people or worse. I haven’t seen a marked increase in any kind of crime in my lifetime. What I have seen is an explosion of the ability of news channels of all kinds to report in almost-instantaneous detail whatever ghastliness there may be almost anywhere in the world.

Truth and Reconciliation

I remember the profound feelings I had when I heard about Desmond Tutu and Nelson Mandela’s Truth and Reconciliation initiative in South Africa. It was an extraordinary idea, to guarantee freedom from prosecution as long as the truth was told. I don’t know whether it made things better or worse, and I don’t know how I would have felt about it if I had found myself part of that, on either side.

There have been lots of attempts in the last few years to implement punishments that involved making some kind of reparation for crimes. There are those victim statements in court, and meetings between victim and perpetrator, and Community Service, and there’s always talk about making offenders make it up to their victims somehow, in an attempt to get them to feel what it’s like to be the victim of crime.

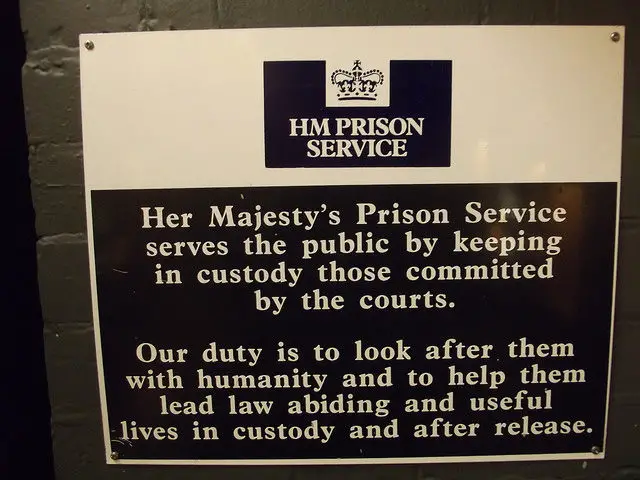

Decrease the number of disadvantaged people

I’m not sure how all this would work, without a lot of training and investment, and the courts don’t seem in any hurry to use such facilities, because our prisons are jammed with people, many of whom really don’t need to be there. It’s also no coincidence that most of our prison population are from disadvantaged backgrounds, and many of them have developmental and/or psychiatric issues.

It always seemed to me that the best way to cut down on the numbers of criminals and crimes, would be to decrease the number of disadvantaged people in society, and make our social systems work better. Good schools, better child-monitoring, help for families who are struggling – these all seem to me to be investments rather than expenses. Besides, it costs more to keep a person for a year in prison than a year at Eton, with considerably fewer good outcomes.

The determination to make things better

Being sorry requires more than saying sorry. It’s like government ministers standing up and announcing great new initiatives that will improve things for disadvantaged people, and it always seems to turn out that they’ve just rebadged things that are already there and not working well. Policies to improve society need to be based on a real desire to do the job properly, to fund it fully, and to carry it through. That’s something we have forgotten how to do.

One of the things we trumpet about our country is the achievements of social reformers. We were ahead of the game in outlawing slavery, and providing universal education, and child protection, and the NHS, and building proper sewerage infrastructure, and making sure that water was safe to drink and air much safer to breathe. These things were born from a combination of vision based on a clear understanding of right and wrong, and the determination to make things better. We seem to have stopped doing that.

To ensure that it doesn’t happen again

The reason why I’d like sorry to be banned is because the whole sorry thing is only a tiny part of the process. First, someone has to be seen to have done wrong, or not very well. Then the actual thing that is wrong has to be described. Then a solution has to be defined, and an action plan has to be agreed and carried out. Saying sorry should be a small paragraph somewhere in the middle of all that.

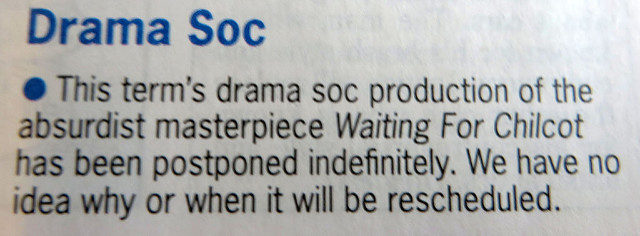

This is what enquiries are all about. Whenever something major goes wrong in public, there’s a long consultation period followed by a report. The report always specifies what actions need to be undertaken to ensure that it doesn’t happen again. Sometimes this is carried out, and a lot of the time it’s fudged, or forgotten, or the enquiry is tampered with or delayed, as in the Chilcot Enquiry.

Saying sorry and hoping it gets forgotten

This process is fundamental to our concept of civilisation, and we need to keep doing it. Sometimes it takes decades for justice to be done. Ask anyone who lost a relative at Hillsborough. The damage we do when we ignore the lessons we need to learn and the improvements we must make always multiplies the damage that occurred originally.

So let’s stop saying sorry. Let’s ask ourselves what went wrong. Let’s be honest. Let’s agree to do something real to make things better. Let’s actually do it, rather than saying sorry and hoping it gets forgotten.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: epmle under CC BY 2.0

Image: ErikaWittlieb under CC BY 2.0

Image: OpenClipartVectors under CC BY 2.0

Image: Public Domain

Image: pictoquotes under CC BY 2.0

Image: ell-r-brown under CC BY 2.0

Image: Public Domain

Image: Gwydion M Williams under CC BY 2.0

Image: aroberts under CC BY 2.0