Jonathan Dodd‘s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

A few years back, on the other side of the millennial divide, I was working for a company called Unisys, in an office building in Slough that resembled badly-stacked plates.

We were mostly busy conducting grammatical arguments with some MoD civil servants who worked in a converted Second World War hospital on the hilly outskirts of Bath. They were supposed to be reviewing our test scripts, but all they ever did was query our use of commas.

His muscles were too hard

I had two project managers in my time there. One was a fitness freak who was jealous of my ability to swim and kept telling me that swimming was impossible for him because his muscles were too hard.

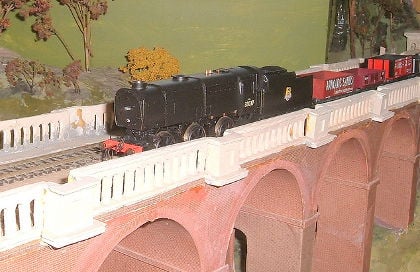

The other one was an obsessive photographer of Victorian railway architecture. Family holidays would consist of bed and breakfasts in Derbyshire out of season and a lot of clambering about to get the best. These were apparently wildly popular on the model railway club circuit.

During the project we were required to relocate for a few weeks to Bath. I commuted for a few days in my barely-alive Metro until I found an advert looking for a short-term lodger. The owner lived in Royal Crescent, in a flat filled with very large semi-architectural oddments. We drove to a village outside Bath, to a building he was renovating with a view to renting out or selling on. It was in a small village in a hollow somewhere off a main road south-west out of Bath.

Looking for a bed somewhere

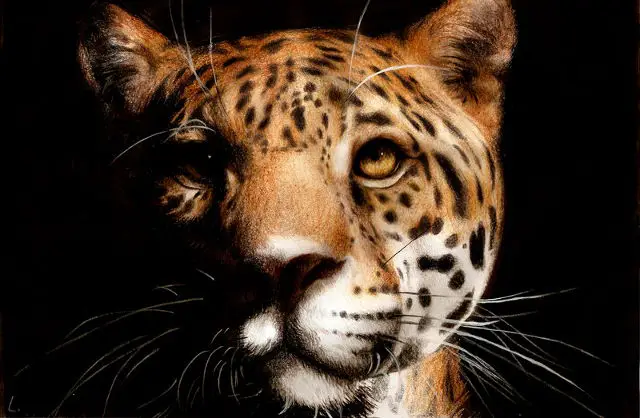

This was during a damp and misty late Autumn, and the village was dark and dripping. We pulled up outside a building with a metal sign depicting a leopard. I was to stay in the middle floor, which was painted all white, and also had various architectural items lying around. My landlord pointed out two very large wooden pillars he had installed in the main room. I nodded enthusiastically, looking for a bed somewhere. There was one, the rent was reasonable, I paid in advance, and he handed over a key.

I spent a few weeks in that flat, negotiating a path through the objects. It reminded me of a holiday in Turkey, with a swim in an open-air spa pool filled with the remains of a large Greek building. You would bark your shins on lumps of underwater Doric column or the remains of toppled statues, while all around people were eating and drinking at restaurant tables.

Like I was living in a Cocteau film

I never saw the leopard building or the rest of the village in daylight. Whenever I returned to it or left in the morning, it was always misty and dark, with the feeble street lights casting a murky glow. Every road out was uphill. I felt like I was living in a Cocteau film.

Once I was driving home and I stopped on a long straight road, partway up the east side of a valley. The road was lined by tall trees, and across the valley I saw a perfect and beautiful white horse carved into the chalk. That was before the era of mobile phones with cameras, and I vowed to return and take a picture. I never found the road or the valley again.

Chorusing their distress in the silence

There was a man working in my team who I had had a premonition about. He was very buttoned-up, much like the old version of Alexei Sayle, with a round face and body and a small moustache and a very red complexion. He never relaxed or moved slowly, and I worried that he was going to have a heart attack.

One morning I was late to work, because of an accident. A lorry full of pigs had run into the back of a small car on the winding and hilly roads round there. No sentient beings were injured or killed, but I remember them chorusing their distress in the silence.

When I arrived at work, everyone was in a state of shock. The man I was worried about had bustled into the office and fallen headlong, bashing his head on the edge of a desk. They said he was already dead as he fell. All that was left was a bloodstain on the floor. Shortly after that we returned to Slough and they cancelled the project. My next job was in Swindon, where nothing weird ever happens.

The building with the leopard sign

Ever since then I’ve been meaning to find the building with the leopard sign again. On our recent trip to Bath I managed to retrace my steps and found the village. In sunlight it didn’t look or feel anything like the same place. Sure enough, the building was there, and I could see the windows of the middle floor, and the old wooden front door in its arched portico. But the sign very clearly didn’t depict a leopard. It was an old greyhound.

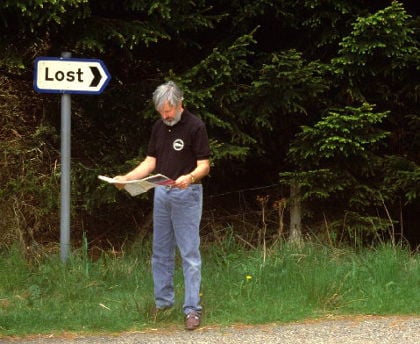

On the way out of there we became completely lost. It took hours to escape that strange landscape to the south and east of Bath, as if the murk of my previous visit was still invisibly wreathing around my head.

Did it all really happen like that?

I started wondering if my memory and my dreams had become commingled, so that each had become as real as the other in my mind as I recalled that strange time. Did it all really happen like that, or only some of it? If a dream or a false memory can acquire exactly the same feel as the actual events, or the actual memory seems dreamlike, how can we know? And does it actually matter?

Is a leopard better than an old greyhound?

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: komorinight under CC BY 2.0

Image: Elsie under CC BY 2.0

Image: Teresa Reynolds under CC BY 2.0

Image: Colin Bates under CC BY 2.0

Image: Dickbauch under CC BY 2.0

Image: Peter Ward under CC BY 2.0

Image: gomagoti under CC BY 2.0