Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

There’s a tired old argument that doesn’t often rear its head so much any more, but was prevalent during my youth, about National Service. It was, said various acquaintances of my parents, often loudly and somewhat aggressively, necessary to do National Service, because – “It makes a man of you”. The trouble is that as far as I could see, the experience of National Service that most people I knew was an exercise in futility and boredom and a complete waste of time.

This is probably because it was run by the Armed Forces, who are not well-known for doing things well or properly, apart from the actual business of fighting and peacekeeping, and are not helped by various Cabinet Ministers. I don’t disparage here the magnificent efforts of many of our troops on the field of battle, and I’m only using this idea to grope my way towards the thing I really want to say, which is about how well we might know ourselves.

Discretion is the better part of valour

My brother was going to be called up for the very last year of National Service, but his University course took four years, so he missed it. He was relieved, as I would have been in his place. Shortly thereafter, he got himself a job in the USA in the early Sixties, which he enjoyed very much, but then his draft papers arrived in the post, causing him to beat a hasty retreat back to England.

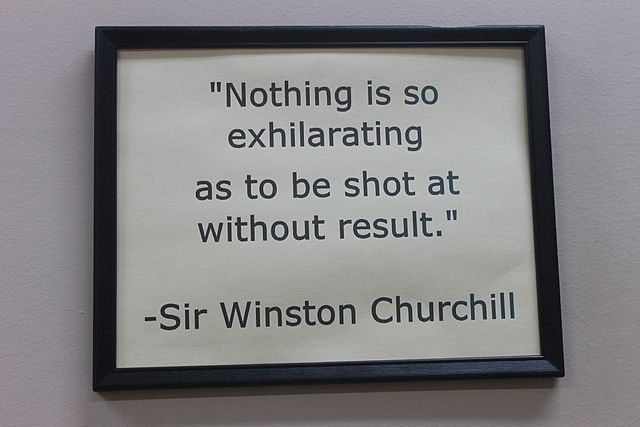

That was the early Sixties. Vietnam was revving up. ‘He who fights and runs away lives to fight another day’, as Bob Marley sang, although it was first said at the time of the Ancient Greeks. Then there’s the ‘Discretion is the better part of valour’ quote. Personally I’d be in favour of the quote that hasn’t been said, which is to find a safe place before hostilities break out. Or even the quote before that, which refers to defusing the crisis before people start preparing for war.

What would I actually do if I was there?

But then, would I run away? This is what I mean here. I can joke about war and fighting and the avoidance of same, and I can be scathing about the ineptness of so-called leaders who mess thing up so far that wars erupt, but what would I actually do if I was there, and was asked to serve? That question was most forcibly thrust upon me when I went to see Saving Private Ryan on a large cinema screen.

The genius of Stephen Spielberg recreated the way it felt to be in the middle of the madness and carnage of battle, as far as he could, with the help of people who were there. All I could think, over and over, as I watched it, was – “In an earlier generation, that could have been me”. I had no idea whether I would have been heroic or cowardly, and I was uncomfortable, because I had no answer to that question. I still don’t.

War is never going to be clear-cut

The other thing I liked about that film was the portrayal of a soldier who was so scared all the way through and was completely inept, to the point where he endangered others. He was accepted for what he was, and ignored while the serious fighting business took place. And there was a scene in which the ‘good’ soldiers committed a war crime without being reported, and then didn’t commit a war crime which resulted in several casualties. War is never going to be clear-cut.

I once heard an ex-army man tell me about battle. I will say at the outset that my memory for numbers might not be accurate, and his idea might be entirely apocryphal, but it felt true. He said that it doesn’t matter how well you train soldiers. They’ll march well, and have clean boots, but when it comes to battle, about 40% of them will discharge all their bullets in the first five minutes, another 40% won’t fire a single round, and the other 20% will just get on with the business.

How we react when things happen to us

I liked that story, because I thought it related very much to my own thoughts and fears about myself. I suspect I’d be in one of those 40% groups, although I would have a one-in-five chance of proving myself wrong. And there’s no actual knowing how finding out would affect me. I think many men are driven mad by battle, and a lot of them never recover.

So, this lunchtime I was reading a book, as I do, and one of the characters was talking about who we think we are. He said that, rather than knowing about ourselves, we only find out by how we react when things happen to us. So when the old soldier was going on about National Service “making a man of you”, what he really meant was confronting the fear of death by being actively and seriously shot at, with intent.

You might be actually shot

There are several drawbacks to this strategy, of course. You might not be shot at, per se, you might be actually shot. Permanently. In which case there’s no wisdom and no knowing. The experience might ruin your life, so you might change out of all proportion, and the knowledge of how you were before would no longer apply. Or you might just possibly discover great reserves of heroism and leadership within yourself that you had no idea were there. I reckon the odds of that are far less than one-in-five though.

One thing we no longer have that used to exist in all societies everywhere is the rite of passage, the formal marking of the transformation from childhood to adulthood. We don’t have to hunt lions or survive dangerous journeys or ordeals any more, but we sometimes have a simplified and far too safe and comfortable version, where the ceremony is more important than the experience. Various churches practise Confirmation, and there’s the Bar Mitzvah, and to a certain extent GCSEs and A levels are filling this void, but they don’t necessarily celebrate the qualities of good old-fashioned rites of passage.

A rite of passage for our times

Come to think of it, I can’t really decide what would or should be incorporated into a rite of passage for our times. We do mark various milestones and achievements. Graduation, the Citizenship Ceremony, marriages, and various others. A lot of them are quite subtle, as in the first time a child comforts his or her parents, or buys them a meal or a drink. Or moving away from the parental home.

My brother took me for a pint when I was fifteen, and it was great, apart from nearly being thrown out of the pub when my host noticed I had a bell round my neck. One did such things back then, some people thought it was cool. I do know that the near-throwing-out was far more significant for me than the buying and sharing of beer.

We did do all those things ourselves

Young people do take risks. As parents we’re rightly worried about them driving too fast, or drinking too much, or taking drugs, or getting into all the scrapes we used to get into before we were parents. And we did do all those things ourselves, or most of them, and that’s why we worry. Now we’ve done them, and survived, we know things about them, and about ourselves, that our young people don’t yet know. And we know they have to be allowed to do or not do them for themselves so they can find out.

I don’t know if we should try to prevent all risk-taking, or whether we could. Risky things happen, either through natural or unnatural cause, or through human stupidity or obstinacy. There are always casualties, despite how hard we work to mitigate the risks. None of us want to become furtive and passive, afraid of anything that might challenge us, but sometimes we allow ourselves to get stuck in a familiar unpleasant place rather than try to escape to another place that might, or might not, be better.

We can’t teach self-confidence, we can only encourage it

I hear of people who stay in bad marriages or don’t apply for better jobs, or put up with all sorts of bad relationships, through fear, or through lack of self-confidence. But we can’t teach self-confidence, we can only encourage it. You get self-confidence by committing to something and seeing it through. You have to have the experience of identifying and overcoming obstacles to become properly self-confident.

We have far more opportunities nowadays to experience second-hand many of the more interesting experiences in life, through books and films and news stories. These stories can inspire us if that’s what we want, or they can confirm our wish to avoid those situations. In this sense, we can use them to reinforce our idea of ourselves as we believe we are in positive or negative ways. I think we should practise the art of challenging ourselves more, and spend less time in our comfort zones.

You’re not necessarily what you think you are

The problem is that real life throws all sorts of complications and crises at us, and these usually come at us out of nowhere. When they happen, and we have no time to think, we find out real truths about ourselves, which are often completely the opposite of what we thought. Sometimes unwarranted confidence shatters, and sometimes a hero emerges from inside the shell of a quiet unassuming person and astonishes everyone, especially the hero. I find that rather comforting.

You’re not necessarily what you think you are. You’re often a lot better than that.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: public domain

Image: billward under CC BY 2.0

Image: Public domain; official U.S. Coast Guard photograph

Image: George Hodan under CC BY 2.0

Image: Billy Hathorn under CC BY 2.0

Image: Steve Evans from Citizen of the World under CC BY 2.0

Image: cherryberry under CC BY 2.0

Image: midiman under CC BY 2.0

Image: vinothchandar under CC BY 2.0

Image: Fair Use under CC BY 2.0