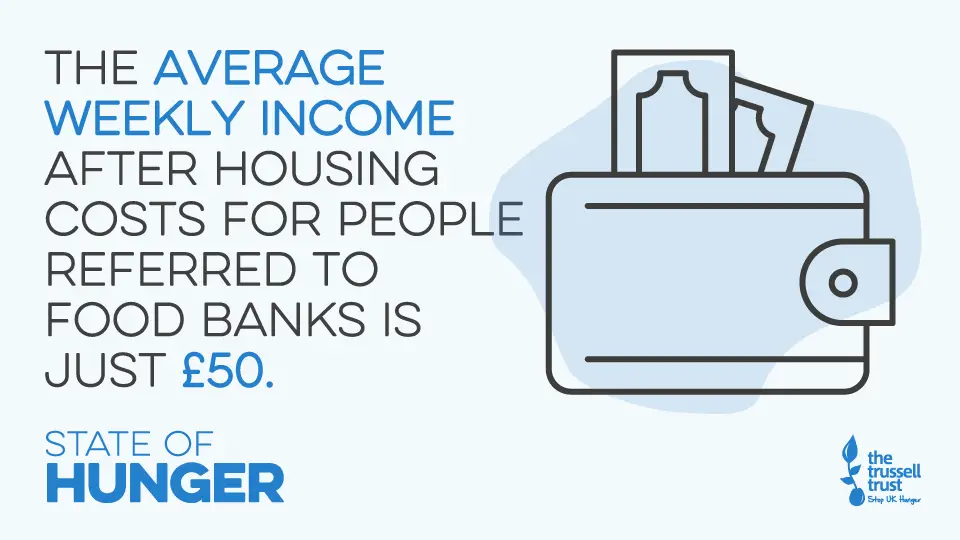

‘Locked in extreme poverty’: landmark research shows household at food banks have only 50 a week to live on.

Commissioned by the Trussell Trust and conducted by Heriot-Watt University, State of Hunger 2019 is the most authoritative piece of independent research into hunger in the UK to date.

94% of people at food banks are destitute

It reveals the average weekly income of people at food banks is only £50 after paying rent, and almost one in five have no money coming in at all in the month before being referred for emergency food.

- 94% of people at food banks are destitute.

- Almost three-quarters of people at food banks live in households affected by ill-health or disability.

- 22% of people at food banks are single parents – compared to 5% in the UK population

- More than three-quarters of people referred to food banks were in arrears.

Isle of Wight picture

Here on the Isle of Wight, the Foodbank revealed in April that on average, 20 Isle of Wight households needed emergency food parcels every week day last year.

According to End Child Poverty (May 2019 figures) there are 9,679 children on the Isle of Wight living in poverty. That’s 34.3 per cent of children, or over ten students in a class of 30. That is an increase on last year’s figures of 29.5% or nine students in a class.

No protection from hunger and poverty

The first annual report of a three-year long research project, it shows definitively for the first time the three drivers hitting people simultaneously and leaving no protection from hunger and poverty.

These drivers are problems with the benefits system, ill health and challenging life experiences, and a lack of local support.

The most common source of income for people at food banks is the benefits system.

Key problems with benefits

Problems with benefits are widespread, affecting two-thirds of people at food banks in the last year. Some of the key problems with benefits highlighted by the research are: a reduction in the value of benefit payments, being turned down for disability benefits, being sanctioned, and delays in payments like the five week wait for Universal Credit.

Statistical modelling shows the positive impact an increase in the value of benefits could have, estimating that a £1 increase in the weekly value of main benefits could lead to 84 fewer food parcels a year in a typical local authority.

Challenging life events

The majority of people referred to food banks also experienced a challenging life event, such as an eviction or household breakdown, in the year prior to using the food bank.

Such events may increase living costs and make it harder to maintain paid work or to successfully claim benefits.

Particular groups of people are more likely to need a food bank. One risk factor is being a single mother – 22% of people at food banks are single parents, the majority of which are women.

The impact of health issues

Almost three-quarters of people at food banks have a health issue, or live with someone who does. More than half of people at food banks live in households affected by a mental health problem, with anxiety and depression the most common.

A quarter of people live in households where someone has a long-term physical health condition; one in six has a physical disability; and one in 10 has a learning disability or lives with someone who does. Ill health often increases living costs and may be a barrier to doing paid work.

“Go to bed wishing I never wake up in the morning”

Amanda explained to researchers that £130 of her £138 fortnightly benefit payment for a health condition goes to paying arrears, leaving her with only £8:

“If I don’t pay my bills, then I’ll get the house taken off me. After paying arrears, I’ve got £8 a fortnight and that’s to pay for gas, electric, water. So it’s just impossible, it really is. I go to bed at night wishing I never wake up in the morning.”

The study also found that the vast majority of people at food banks have either exhausted support from family or friends, were socially isolated, or had family and friends who were not in a financial position to help.

Revie: People trying to get by on £50 a week

Chief Executive, Emma Revie, says:

“People are being locked into extreme poverty and pushed to the doors of food banks. Hunger in the UK isn’t about food – it’s about people not having enough money. People are trying to get by on £50 a week and that’s just not enough for essentials, let alone a decent standard of living.

“Any of us could be hit by a health issue or job loss – the difference is what happens when that hits. We created a benefits system because we’re a country that believes in making sure financial support is there for each other if it’s needed. The question that naturally arises, then, is why the incomes of people at food banks are so low, despite being supported by that benefits system?

“Many of us are being left without enough money to cover the most basic costs. We cannot let this continue in our country. This can change – our benefits system could be the key to unlocking people from poverty if our government steps up and makes the changes needed. How we treat each other when life is hard speaks volumes about us as a nation. We can do better than this.”

Changes needed

The Trussell Trust is calling for three key changes as a priority to protect people from hunger:

- As an urgent priority, end the five week wait for Universal Credit

- Benefit payments must cover the true cost of living

- Funding for councils to provide local crisis support should be ring-fenced and increased

News shared by the Trussell Trust, in their own words. Ed