Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I recently wrote about growing up in Hove all those years ago, and I realise I was quite rude about it. That’s what happens when you tell a story. You’re trying to make a point, and you find something that illustrates that point. Then you’re off and having fun, riding the thought, the ideas whipping round your head, and the scattered words starting to coalesce into sentences for your hungry fingers to type down as fast as they come. Thank goodness for spellcheckers, that’s what I say. But, while this is a good way to get columns written for OnTheWight, it doesn’t necessarily tell the whole truth about the thing that was chosen, and maybe sacrificed, for the cause of the idea.

What I thought after I wrote it, was this. First, Hove was just the vehicle for getting the idea written, and not the idea itself. Let’s not shoot the messenger here. Second, I started thinking about the rest of my childhood experiences, and it opened doors that I had forgotten about. The thing about memory is that you never forget anything. It’s just difficult sometimes to recall things without the right cue. Memories work by being attached to thoughts and experiences. If you remember something randomly, that memory jumps to other memories, related in ways you can’t remember actively, and you can go back into a whole world you thought you had forgotten. Or maybe you just hadn’t thought about it for a long time.

A time that’s already becoming unrecognisable

My column brought back lots of these memories, and I’ve been enjoying rolling out these threads of memory, making my way through the labyrinth of my memory databanks, brushing off the dust and opening the curtains of rooms I hadn’t visited for ages. I suppose it’s like living in a palace. You have so many rooms, but you don’t usually use more than three or four. How often do you go to visit all the other rooms? Mervyn Peake wrote a whole trilogy about this in Gormenghast, a vast decrepit city of a building that seemed to go on for ever. I also remember watching the Leopard, an Italian film about an Italian grand family fallen on hard times in Sicily in the nineteenth century, in which an absurdly young Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale explored room after room that hadn’t been visited for ages, filled with old furniture and covered in dust. It was a jolly good film, one of my favourites.

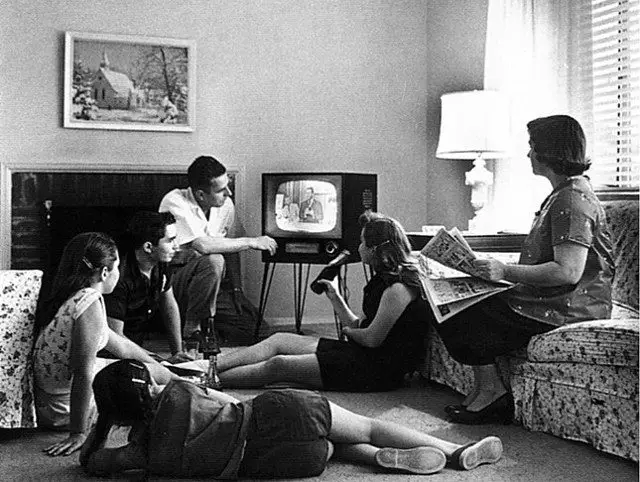

I’ve been on a similar journey, back in Hove during the second half of the twentieth century, a time that’s already becoming unrecognisable, even to those who lived in it. I remember the lack of traffic, and the excitement of buying new shoes or clothes, and the need for my mother to cook every meal from ingredients, and the black and white TV with its small screen, and the antenna that had to be adjusted and fiddled with all the time. Life was really so much simpler, and people lived so much more locally. My world was bounded by a few blocks, the local shops, and the bus that took me to Brighton. Things could be happening anywhere in the world, or even twenty miles away, and we would all be blissfully unaware of them.

You don’t want to know about that

This wasn’t necessarily a good thing. Prejudice wasn’t even a thought that occurred to anyone, but heaven help you if you were different in any way. You would have to disguise your difference, and there were real consequences. Needless to say, I knew nothing of this at the time, because all those new parents who had lived through the Second World War wanted nothing but a better world and to forget the horrors. You can understand this, but my parents never ever talked about any of it. Whenever I asked them about the past, their answer was always “You don’t want to know about that”. But I did, I did.

I remember now hearing talk about Jews, or Blacks, or Pansies, with an underlying desire to avoid them. There was a couple up the road, and one day the wife, who everyone always described as ‘suffering from nerves’, tried to drown herself. My father got his name in the papers by wading into the sea and hauling her out. But nobody ever spoke about it. If you were any of these things, you hid it and hoped nobody would ever find out, because that would mean disgrace, the loss of your job, and social banishment. I don’t know why this happened, and I knew nothing of it at the time, living in Janet-and-John-Land.

It alienated me from my parents

Later, I would walk home late at night along the seafront, and there would be men sitting in the sun shelters, and I would stop and chat to them, completely oblivious of their gayness and the risk of being discovered down there. I knew nothing, even then. Nowadays Brighton celebrates openness about lifestyles and choices, and I suppose there was always an underground there until it became decriminalised (the criminalisation something that should never have been allowed to happen). I always remembered how deeply sad and alone those men were, and how they were so eager to talk, and how polite and careful they were, and how frightened.

I’ve always championed minorities, and I really think this comes from my shock when I realised everything that stood behind my late-night conversations on the seafront. I was protected by my innocence, and my head was too full of music, and girls, and alcohol otherwise. I had always felt so safe, and so grounded, in the small world my parents built round me. It was such a shock to realise that people, even in my own road, might be living in fear, hiding their real selves behind a cloak of normality, and this made me sad, and sorry for all the outsiders, and a little guilty of my own privileged life. And it alienated me from my parents, because they closed off so many areas of life that I was interested in, and they lost me.

At the heart of all prejudices there are absurd contradictions

Having said all that, there was many advantages to being me and there. One thing which contradicted and expanded my outlook on life was my mother’s job. There were no job opportunities in Hove, or so it seemed, and all the husbands and fathers trooped off to catch the train every day to London to work in offices in their suits. If you needed extra money you took in Foreign Students. My mother wasn’t the type to sit around, and she prepared a couple of bedrooms for this very use. She was successful, and we bought a bigger house, nearer the sea, with more bedrooms. Soon the house was more or less continuously filled with manly young people from all round the world. You’d have thought having so many odd people from exotic places wouldn’t sit well with such careful and conservative values, but at the heart of all prejudices there are absurd contradictions. Besides, it brought in money.

I was unaware of any of these considerations however, and I loved it. My mother was always busy, so I had more unsupervised time, and I could spend all the hours down on the beach, apart from specific jobs, like laying the table and putting away afterwards. I was the youngest, so my mother always washed up, and my two older brothers dried up, and I had to Put Away. There was a Breakfast Room between the Kitchen and the Pantry, and I wore the floor out walking up and down, carry a plate or two each time. I argued constantly that I could wait until a stack appeared, but my mother insisted on me carrying whatever had been dried since I last set off. I think she didn’t like me wasting time, and probably she decided I couldn’t break more than one thing at a time. Not that I ever did.

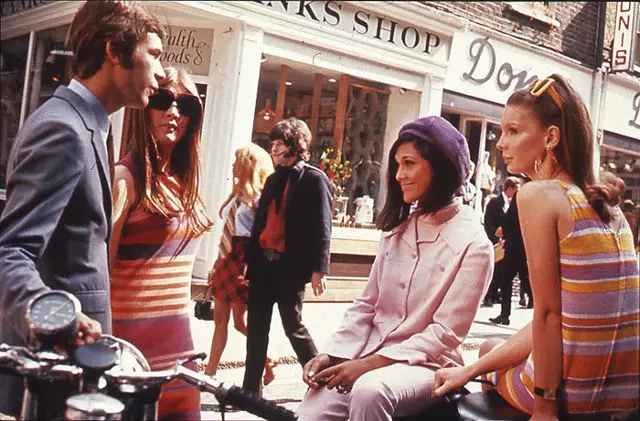

Everyone else seeming to be eternally teenagers

I can’t imagine how much hard work my mother had to do to keep this constant assembly line of students happy and comfortable. Because they were all young, part of her job was to stand in a sort of In Loco Parentis, so she treated them like her children, and they thought of her as a second mother, which either made things smoother or turned into more trouble. She had a book, in which everyone wrote when the went home after their month or year in our house. There was also a photograph album, with constantly changing groups standing in the small front garden squinting into the setting sun, with all of us getting older or growing up, and everyone else seeming to be eternally teenagers, dressed in ever-changing fashions.

For me, it was a form of enchantment. I got to have new friends all the time, who spoke either good English that became practically perfect, or no English at all. I watched them learn and improve, from day to day. And I was a part of that. I became adept at understanding what people were really trying to say, and my own conversation became very concise and clear, and my ear sharpened for pronunciation and the nuances of different languages and accents. They were just like us, of course. They might be surly or happy, innocent or scheming, lonely or sociable, they might hardly ever open their mouths, or they might never shut up. We would go out in a gaggle – three French, two Swedish, maybe a Greek and a Spaniard, add in an odd Italian or Finn. Every sentence in every conversation would be translated at least once. Occasionally someone would arrive from Africa, or South America, or Japan or India, or even Sarawak, which we had to look up in the Atlas. I could identify the nationality of anyone from a distance, from the clothes they wore. It was wonderful and exotic, and strangely normal, because it was happening all over Brighton and Hove.

The influence of foreign practices and beliefs

There’s a lot of talk about multiculturalism nowadays, and how the world is getting smaller, and more people are getting used to a world in which they have to deal with at least some strangers or foreigners. But at the same time, there’s still hatred and suspicion, like it was when I was growing up. I’m sad about that, because the world I saw was one filled with wonder and fascination. I learned that there’s no language barrier, unless you decide to erect your own. I felt for many years that the world was becoming one world. Perhaps I was naive, or perhaps not enough people have had my undoubted advantages in spending time with so many people from so many countries.

These last few years have been a shock to me, because of the sudden upsurge of anger and resentment that we’re living through. Suddenly it has become acceptable to express these emotions in public, and I’m horrified and embarrassed that my countrymen think this is a good thing, not only to say it, but to campaign to shut ourselves away from all other countries, as if we have to cleanse ourselves of the influence of foreign practices and beliefs. What has gone wrong? Or was the idea of living together in harmony just a stupid dream?

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: © Jonathan Dodd

Image: public domain under CC BY 2.0

Image: gaabriellablee under CC BY 3.0

Image: Hassocks5489 under CC BY 2.0

Image: inkknife_2000 under CC BY 2.0

Image: The National Archives under CC BY 2.0

Image: dullhunk under CC BY 2.0