Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

It’s not very often that I find myself completely astonished, and at a loss for words. In fact, anyone who knows me already knows that my mouth is like a swollen river of words in full flood. I’ve understood over the years that there are two types of people in this world, and one of those has trouble with the amount of talk I come up with. It’s just a fact of life, at least my life. I’ve tried to stop talking so much, but my interior talk tap hasn’t got a washer. It’s either on or it’s off. And to tell the truth, I worry about turning it off, because of the build-up of pressure from all the things in there, queueing up to be said.

This is, of course, far from being my only fault, if fault it be. And I have another channel for this flow, and you’re reading this because I’m also able to let it pour out onto my screen. I never could get the point of writing things down on paper. Back at school, the idea of rewriting essays before handing them in was uncontemplatable, and I know I would have got better grades if I had a word processor. But sadly those hadn’t been invented then. There weren’t even any computers that didn’t occupy whole buildings, so I was pining for something that was only in the unforeseeable future.

That pair of shoes in the window of that shop

There’s an interesting idea. We all pine for something. Some of us know exactly what we’re pining for, and there’s a sort of comfort in that. If you want that pair of shoes in the window of that shop, it’s easy. Either you can afford them or you can’t. Life can be simple. However, if you’re desperate for a particular pair of shoes, and you can’t find them anywhere, you’re pining for something that you just can’t find, sometimes even with the Internet’s help. That’s frustrating, but it’s still simple.

The third kind of pining is harder, because you know that something is frustrating you, but you can’t see an answer. If only someone would invent a thing so you can fish your dropped Clubcard from between those floorboards, or get the last bit of toothpaste from the tube, you’d feel better. But they haven’t. Back at school I was pining for something to take away the pain of writing on paper with a fountain pen, and I had no idea what the alternative might be. It was so frustrating.

Written wordy splurges as well as spoken monologues

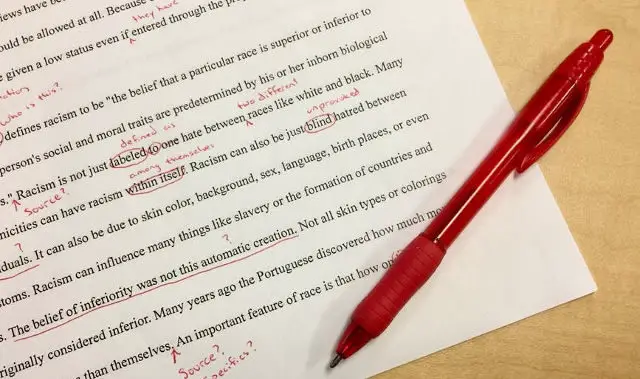

When I first saw a word processor, I fell on it, and my writing life began. Ever since then, I’ve been able to bother at least half of those members of the human race that I have encountered with written wordy splurges as well as spoken monologues. And I can edit. If you could see my screen, it’s covered with those little red squiggly lines, and blue lines, and brown dotted lines, whose reason-for-being I cannot guess at. I tend to just start tapping the fingers without thinking about what’s actually appearing.

I like the freedom of walking away from the process, if process it could be called, when I start writing, and my fingers dance over the keyboard with gay abandon, and I don’t even look up for what seems like ages. Everything gets resolved when I’ve finished, by the editing process. First the paragraphs, then the spellcheck, then the grammar and punctuation check. And somewhere during all that, those pesky brown dotted lines disappear too.

Going to write about one thing but ended up with another

Sometimes I find myself remembering through all of this that I was going to write about one thing but ended up with another, and then I have the fun of trying to reconcile the two themes, with occasional moderate success. I just remembered that I was completely astonished, and speechless. That was when I was watching a TV programme about a fatberg autopsy. I love that title. How could you resist a programme called FATBERG AUTOPSY? It was one of those shudder-inducing things you never really heard of, or thought about, brought all-too-vividly to life in your mind. It was riveting, and hideous, and my gob was well and truly smacked by it.

Here’s the set-up. The presenter arrived at a street somewhere in South London, late at night. There was a gang of men in lots of Day-Glo, standing round an open manhole. They were there to clear a fatberg. This one was the largest ever recorded, stretching over a kilometre under the streets, blocking an entire sewer. So far, so B-Movie sci-fi shock-horror thing. So they sent a man down to investigate, with an alarm that would tell him if he was breathing lethal poisonous gas, and he reported that he had reached the fatberg. And there it was, a huge off-white crusty mass, a bit like the top of last night’s apple crumble, filling the tunnel, for over a kilometre, as far as the eye couldn’t see, obviously.

A team of crack scientists

The job of the crew was to break it up and allow the sewer to flow again, before it started backing up into someone’s kitchen. The job of the TV presenter was to collect 5 tonnes of it and take it to a disused water treatment plant so a team of crack scientists could study it. Down in the sewer, the men got busy with spades, because there isn’t any other way to break up a fatberg. The smell was awful, and every now and then they had to retreat because of the gas, and after they had scratched the surface of the job and extracted the 5 tonnes, we left them to it.

The fatberg sample was laid out on a large table, and a team of workers started to break it up into ever-decreasing chunks. They separated out all the objects from the basic crust mas, and then they analysed it. To put it bluntly, a fatberg is almost all made up of cooking oil, dumped down the drains by restaurants. In itself, this is not too bad, but the oil reacts with the calcium in the water, which makes it turn into grains, which stick together. Everything slows down, and turns into a mass, which just keeps growing, until it seals the sewer tunnels.

Specialist fatberg-clearing teams

Fatbergs are an urban phenomenon. Most of our cities have them now, and most of our cities now spend a lot of money on specialist fatberg-clearing teams, who go down and dig them out at night. These men are hearty types, who spend a lot of time joshing each other, but they know it’s dangerous, and they watch each other’s backs. They’re not going to get any medals, but they should. It’s filthy, unending, dangerous and exhausting work, done during the most unsociable hours, and they indulge in a sort of quiet graveyard humour about it. How else could they cope?

If it was just cooking oil and water it wouldn’t be so bad. Unfortunately, mixed up and embedded inside this massive pile of awfulness you will find used syringes and contraceptives, any object small enough to be flushed down a toilet, many different substances that I won’t go into detail about, and wet wipes. The wet wipes are the glue to which the congealing oil attaches itself. They provide the mesh that allows the fatberg to become larger and more solid.

Most people who use wet wipes aren’t aware of this

Wet wipes were never meant to be disposed of in that way. Toilet paper dissolves and comes undone in water, but wet wipes don’t. Their packaging says they’re flushable, and the manufacturers say that they mean the wet wipes will disappear down the bend after flushing, which is disingenuous of them, to say the least. Most people who use wet wipes aren’t aware of this, or prefer to pretend they didn’t know. And, without the congealing cooking oil, they would only be a small problem to sewerage workers, so it hasn’t become a crisis before.

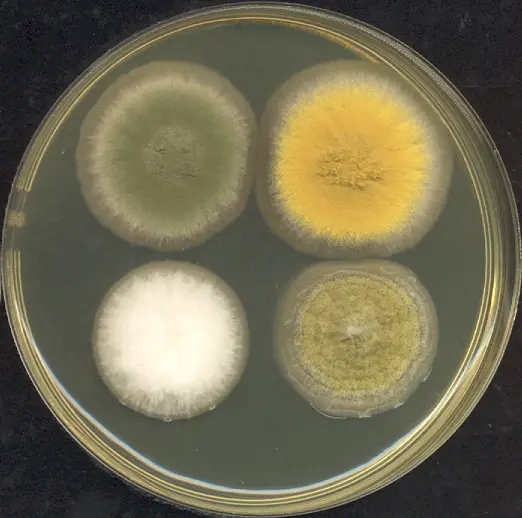

As if all this wasn’t already gross and unpleasant and dangerous enough, the team doing the fatberg autopsy was also searching for life inside it. And they found plenty. Apart from all the usual vermin and worms, a lot of microbes and bacteria were present, everything that can cause stomach upsets and other infections, such as listeria and e-coli. There were rather a lot of antibiotic-resistant bacteria as well, including some that the expert hadn’t ever come across. There they were, in antibiotic-resistant heaven, breeding and mutating like crazy, down in the dark, under our streets, unseen. In fact, the face of the biologist who discovered them was the most searing image of the whole programme, as he held up a Petri dish full of antibiotics, which hadn’t killed any of these new bacteria strains. I could hear them sniggering.

What do we do about cooking oil?

As with the discovery of the plastics that are filling our oceans, we are quick to take up new materials, but very slow to notice that they may not be as wonderful and convenient as we first thought. Sometimes we can act quickly and effectively, as when the ozone hole was discovered, and the use of CFC gas was discontinued, and all the aerosols were changed. Sometimes we can realise that encouraging diesel cars was a mistake, and start to put it right by making them less attractive to buy than other cars. We can probably force the wet wipe manufacturers change their products so they break down quickly in water. But what do we do about cooking oil?

If you work in a restaurant and you tip your cooking oil down the drain, who’s to know? How can anyone point the finger at you, especially in a London street with 30 restaurants. And, in the privacy of someone’s bathroom, who’s going to be able to stop someone flushing who-knows-what down the toilet?

I think it’s worth that effort

In the end, it’s up to each of us, when we get the information, to change our habits and make an effort. We’re rather good at this, in fact. Nobody has really complained about having to buy plastic bags, after all. And there are always going to be some people who won’t care, or who take a perverse pleasure in doing the thing they’re not supposed to. Making that minority as small as possible takes a lot of effort, and it’ll never be perfect. But I think it’s worth that effort.

I shall never drop anything down the toilet again without thinking of those men hacking away at the fatberg in a sewer under a street, in the middle of the night.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: Netojinn under CC BY 2.0

Image: pxhere under CC BY 2.0

Image: pexels under CC BY 2.0

Image: pxhere under CC BY 2.0

Image: Urcomunicacion under CC BY 2.0

Image: Lewis Clarke under CC BY 2.0

Image: Adrian J. Hunter under CC BY 2.0

Image: Lord Belbury under CC BY 2.0

Image: Vuong Tri Binh under CC BY 2.0