Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I was never much good at figuring out what was going on around me. There have been moments when I spectacularly failed to recognise the most obvious elements of a situation, and I didn’t have any clue as to how or why I was so obviously out of touch with things that seemed so straightforward and natural to everyone else. Or at least I assumed that this was the case. I have since come to wonder whether they just found it easier than me to look and sound like they knew what they were doing.

Perhaps I’m misinterpreting this right now and here, in a most public way. Maybe everyone feels like this all the time, and it’s the absolute baseline feeling of all our lives. But that still makes it weird, because you’d think someone might have mentioned it, or taken it on themselves to get it through my thick skull. Mostly, I’ve been accused of having a thick skull, not capable of understanding the simplest of things. My usual reaction to this, and the one that has always got me into the most trouble, has been to ask them to explain it to me, so I can understand.

It didn’t seem like an unreasonable request

I remember at school, being punished for the umpteenth time for not having the middle button of my jacket done up. I tried to explain my predicament. “Please tell me why I have to do this, so I can understand why, and then I know I’ll always remember”. That was exactly what I was thinking, in the circumstances, and it made complete sense to me. It didn’t seem like an unreasonable request. Surely in an ordered universe such a thing would be reasonable or even laudable I was trying to be a model citizen, avoiding getting into trouble, breaking rules, taking up the time and trouble of busy people with more important business to see to.

But sadly, it only ever led to being punished twice, once for disobedience and once for impertinence. I managed to stop myself from asking them to explain what they meant by impertinence, mainly because it was a truth universally acknowledged in that school that any refusal to obey would be escalated, upwards and upwards, leading eventually to expulsion, social disgrace, the wrath of one’s parents, and being cast out from the promised future of university and profession and financial security, then presumably a popular funeral ad the arrival at the pearly gates, accompanied by a brass band, including, hopefully, 76 trombones.

Obey the rules as a matter of principle

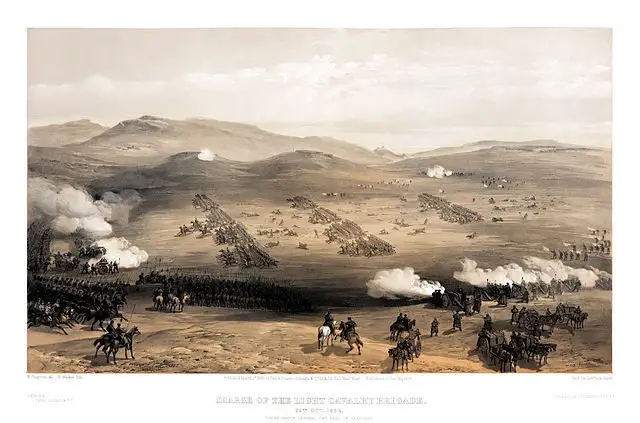

If only I’d known then what I know now. I do know that the expulsion threat was real, and the mindset behind the ridiculous rules was to encourage us all to obey the rules as a matter of principle. On a league, on a league and all that. The Charge of the Light Brigade as a triumph of valiant military honour and discipline, rather than a careless order sending them down the wrong valley right at the massed guns, into the Valley of Death, and the refusal to admit that the order was mistaken. My hindsight-ridden mind sometimes wishes that I had stuck to my own guns and not backed down, but sometimes I think it provided me with the engine for my resistance and that sheer doggedness, which has saved me in so many ways since.

There are moments in particular that my mind returns to, with a combination of continuing perplexity, as if there’s still something there that I haven’t grasped, even though it might just be that particular feeling at that moment that I mostly remember. Here’s one. Make of it what you will. I was never very good at sport. I think you’ll have gathered that by now. Nobody explained to me what the purpose of it was, and it became something that adults made you do, filled with arcane rituals that made no sense, and activities that seemed to make sense to some people, but they weren’t going to share that, because it was always much more fun to shout at you for being an idiot than to explain what you could do to become less than an idiot. Perhaps those people never understood that teams work better if everyone has a good idea of what it’s all about, or maybe they just loved being better than anyone else, or liked the glow of the P.E. teacher’s praise too much.

Adults made you do things, hat was what they did

Take football, for instance. I didn’t come from a sporting family, and my brothers were both much older than me, and my chief exercise-related activity was riding my wood-and-metal Triang scooter up and down the pavements of my road as fast as I could, veering round the darker pavement slabs, and trying not to run into old ladies with string shopping bags or neighbours out walking their dogs. Once a week, my school trooped off the local recreation ground for Sport. This involved putting on great studded leather boots and lining up while the two best footballers started to pick their teams. One by one, their beady eyes would run across the dwindling row in front of them, and there was always a rump of fat or glass-wearing or cack-handed losers left. I was always either the last or next-to-last to be chosen.

I didn’t really mind at that pre-teen age, because things happened and I was either there or not there. There was no questioning usually. Adults made you do things, that was what they did. You either did them, or managed to avoid them, or got in trouble for not doing them. You didn’t even feel that you had a choice in this, it was all random. I was obviously not sporty, and my mind wasn’t engaged on the purpose of this football activity. There was usually a fuzz of childish bodies running around the ball wherever it was, with a few boys actually ever touching it and the rest just following around just trying to keep up. Those of us who had no chance would stand around, because we only got shouted at if we weren’t where we were supposed to be on those occasions when the ball and its accompanying crown swerved towards us.

That’s where those studs came in useful

I was always Left Back. There was a joke at the time. “That’s me – Centre Forward in Football, Left Back at Schoolwork!”, but I was the opposite. I knew there was a point on the pitch where I was supposed to stand, but I knew I wouldn’t remember where it was if I left it for any reason. So, obviously, the thing to do was to mark my position in some way, and that’s where those studs came in useful. The idea that they were supposed to make you run faster on a slippery surface was never going to be applicable to me, because I was never going to get within ten yards of that ball anyway. Besides, I couldn’t kick straight, and I was over-weight.

So I would stand in my position, and I would scuff up the grass with my studs, to make a muddy grassless shape the same size as my feet, so nobody could see it when I was standing there, and I could always return to it after making a pathetic attempt at tackling whatever muscly forward was bearing down on me magically dribbling the ball in front of him, before majestically sailing past me and scoring a magnificent goal, earning himself more glory and praise, and earning me more derision. It was a system of sorts, and it worked, or so I thought. But as with all systems, something had been missed out of the calculations.

It was just another afternoon of Sport

One week, un-noticed by me, there was a council employee on a large motorised mower, on the next-door pitch. Up and down he went, and round and round the buzzing crowd went following the ball, and I stood still on my personal footprint, dreaming about something or other, half-heartedly keeping one eye on the events, just in case I had to attempt a tackle, wondering what it would feel like if I actually by some miracle managed to get my foot to it, and knowing that I would then get tackled myself, and no doubt there would be consequences for me in the changing-room afterwards even if I did. In other words, it was just another afternoon of Sport, and then that moment happened.

Miraculously, the mower was right next to the touchline, closest to me, and the progress of the ball swerved towards me, and set off at a lumbering canter towards it, trying to look manly and self-assured, and failing dismally, and then stopped, like everyone else, because the air was rent by furious shouts. When I turned round, I could see that the groundsman had stopped his mower, and was striding across our pitch, with his pipe in his hand, pointing at my small patch of scuffed earth, and shouting, demanding to know who had ruined his beautiful pitch by making great holes in it. I don’t think there was a finger in the whole park that wasn’t pointing at me at that moment, even the P.E. teachers, and I just had to stand there and be shouted at, by everyone, for what seemed like a long time, and I had nothing to say, no answers to any of the questions shouted at me, and no defence for all the things that were said to me about myself and my attitude and my inattention, and my lack of team spirit, and my lack of being sorry for what I had done, and so on and so on.

Needed for making up the numbers, but otherwise to be ignored

It was all true, of course. I had none of those things. But what I didn’t know at that time was that I also didn’t have any teaching or explanation of what it was all about, or training in any skills I could have used in a sporting situation, and no encouragement to exercise or eat less. I had no understanding of even the most rudimentary rules or objects of the game of football, and nobody ever thought of asking me what I wanted or thought or felt about any of it. So I had no way of explaining what I had done, no context in which I could explain it in a way they could understand, and I had no defence against their sheer anger, because I didn’t know why they were so angry. I still don’t.

![]()

I don’t think I would ever have become a proficient footballer. Perhaps being right-handed and left-footed was part of it. My head always knew what needed to be done, but my feet could never get it right. I learned that later, and I absorbed some of the rules of the game later too, and I even learned to see some of the grace and skill that’s possible in it, occasionally.

Perhaps I was just unlucky with the P.E. teachers that I encountered in my school life. Every one of them was obsessed with winning and with those who showed natural flair for sport, and everyone of them wrote off all the rest of us as necessary unfortunates, needed for making up the numbers, but otherwise to be ignored. No wonder I had a negative attitude for sport of all kinds.

Weirdly, at quite a late stage in my life, I’ve recently become a fan of running. I do sometimes wonder what I might have made of it had somebody encouraged me several decades ago.

If you have been, thank you for reading this. Here’s a jolly song about Sport, by the wonderful Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band. I hope you like it.

Image: David Brown under CC BY 2.0

Image: prayitnophotography under CC BY 2.0

Image: public domain

Image: John A. Coffey under CC BY 2.0

Image: Oliver Dixon under CC BY 2.0

Image: Pixabay under CC BY 2.0

Image: MaxPixel under CC BY 2.0