Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

Every now and again in the history of man, a great hero and exemplar is born. Just being really good at something isn’t always a thing that is recognised or valued, and we have no record of those who never survived childhood, or who weren’t allowed, to recognise and achieve their own particular unique greatness. We don’t have a great history of treating our best people well.

It wasn’t so long ago that the Catholics, bless their little cotton socks, actually apologised to the ghost of Galileo, many centuries after imprisoning him for heresy for suggesting that the sun was at the centre of our universe. It wasn’t a full-blown apology, like “We were wrong, we’re sorry”, but in its own woolly and roundabout way it did recognise the wrong it had done. I have a long list of similar apologies I would like to see on record.

The world would be a much better place, and we’d all be a lot happier

There’s an endless list of people whose lives have been destroyed or warped by regimes, going back all the way to our furthest ancestors. Ordinary people, as well as geniuses, and not just wiped out for stupid reasons, like wars and genocide and generally malevolent stupidity, but even targeted because they’re brilliant. I’ll never understand what motivates those in power to do this, and I’ll never understand those who support such regimes. If we spent half the resources helping people to grow as we did trying to destroy their live, the world would be a much better place, and we’d all be a lot happier.

There’s obviously something wrong with me, because this seems to me to be the simple most obvious idea we’ve ever come up with, but whenever I get into a discussion with almost everyone, they all start off with “I’m as liberal as the next man”, and end up with all sorts of abuse, based on the refusal to let anyone from somewhere else even vaguely threaten our so-called ‘way of life’. It’s an easy call for me, and I suspect there’s a lot of uneasy guilt going on behind the cloud of increasingly virulent verbiage.

Letting go of any of our carefully-protected advantages and privileges

We reveal our insecurity and our lack of willingness to actually implement our convictions when we limit the life chances of others, especially if it might mean letting go of any of our carefully-protected advantages and privileges. Nobody actually thinks that cutting free school meals and limiting welfare to the most vulnerable is good, or morally correct, but the politicians keep doing it, and the voters keep putting them back in power. So we have to live with it, or change the system. That’s an old discussion, and not for this particular column on this particular day.

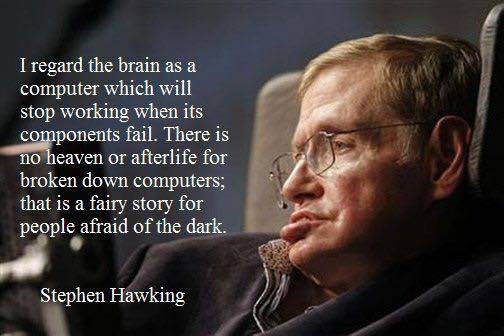

But occasionally we get it right. Perhaps more by chance than planning. A young man by the name of Stephen Hawking had a decent education and was recognised as something of a genius, so he progressed to Cambridge University and began a glittering career, with universal belief that he would go far. And everything was going well for him, when he was diagnosed with a form of motor neurone disease called Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis, or ALS for short.

When the talent is so great it becomes a thing of tragedy

We all feel terribly sad when any young talented person dies or becomes very ill, because of the waste of talent and the unfinished business, and the work hardly begun. But when the talent is so great it becomes a thing of tragedy. We mourn great artists or musicians or writers whose lives are cut short, partly because of their potential, but more so when we catch a glimpse of that potential. In Stephen Hawking’s case, the disease was destined to paralyse him very quickly, and he would lose the means even of speech, so he would be locked inside himself, without the means to communicate the work that his mind was still capable of.

He was also, famously given a very short amount of time to live, and that was back in 1963. He was given two years. I can’t imagine how that would feel, for myself, at my great age, knowing that I’ve done all I’ve done and probably wasn’t destined for any kind of greatness, and not having ever had a flame of light and intelligence inside me that I suspected could be a force for good, or knowledge, or our understanding of our place in the Universe, and what that Universe was all about. But to be him, then, with all of his possibilities cut off at the ankles, that must have been a hard thing to bear.

The most instantly recognisable voice on the planet

We all know what actually happened. He managed to beat those odds, and he live a further five decades, and produced brilliant work, and he overcame, with the help of many others, all those insuperable obstacles. He ended up with the most instantly recognisable voice on the planet, a voice synthesiser made specially for him, with a keypad that he could write with, one letter at a time, painstakingly. It took many years to perfect, and he ended up typing by twitching a muscle in his cheek. He was offered an improved voice, but refused, partly because he was now so recognisable, but probably because it reminded him of his delicately-balanced journey through life, constantly on a cliff-edge between life and death.

The whole world became in awe of him. Not only because of his utter brilliance in his chosen field, but because he became a symbol of the resilience of the human spirit. Leaders queued up to be photographed with him. He wrote several best-selling books about the most complex scientific concepts. I tried to read A Brief History of Time, and I loved it, even though it made my brain feel like it had been run through a spaghetti cutter, and I never understood any of it. I just kept thinking of how he wrote it, with his cheek, and how impossible it was for me to imagine him holding all of it in his head, with no recourse to notes or paper.

At the furthest reaches of time and space

He went on to have two marriages and three children, and lived an extraordinarily full life. He travelled all over the world, gave many speeches, received countless prizes and honours, and was feted wherever he went. He became a sort of icon to the whole world. And he kept working, at the furthest reaches of time and space, all of which were alive and working inside his brain.

There’s another thing about Stephen Hawking that was even more extraordinary. He had a pure, playful joy in life itself, and its possibilities. He loved people, and his family, and his work, and he had a wonderful sense of humour, and he was very sharp. He made television documentaries, and he appeared in a large number of films and programmes, from The Simpsons to Star Trek, his voice appeared on a Pink Floyd track, he worked with Monty Python, and his final appearance was in the latest Hitch Hiker’s guide to the Galaxy, on Radio 4, as the voice of the Book. His story was recently made into a wonderful film, with Eddie Redmayne playing him in an Oscar-winning role.

Our desire overcome everything in our way

How it is possible to live a full and wonderful life was most evocatively demonstrated when a special trip was organised for him on a zero-gravity training aeroplane. Nobody who has seen the pictures of him, floating weightlessly with the biggest grin you’ve ever seen on his face, could possibly not be moved and astounded. That must be the ultimate symbol of our desire overcome everything in our way, to fly to the stars, even though we have no wings. But when we want it, we can do the most extraordinary things, and give ourselves and others the most wonderful hope by our own example.

Stephen Hawking had one of the greatest gifts it’s possible to imagine, and it was so nearly taken from him. He triumphed over adversity, heartbreak, despair and fear, he kept working and achieving his potential, and throughout, he remained bright, charming, and full of life and mischief. I wonder, if Stephen Hawking had been given the choice, whether he would have chosen to live an ordinary life without disability or accept the life he has had. I suspect his work would have been the last thing he would have sacrificed. I’m grateful to him, for his life, his work, and his shining example. If he’s up there somewhere, I’m sure he’ll continue to have fun, and squeeze every moment.

We shall sorely miss him.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: lwpkommunikacio under CC BY 2.0

Image: Ggia under CC BY 2.0

Image: BBC Two via lwpkommunikacio under CC BY 2.0

Image: joshuatree under CC BY 2.0

Image: Magic Madzik under CC BY 2.0

Image: epicfireworks under CC BY 2.0

Image: Jim Campbell/Aero-News Network under CC BY 2.0