Isle of Wight parent and tech geek, Carl Crawley, got in touch asking if we’d share this research he carried out today about the MOMO suicide warnings that are doing the rounds on social media at the moment. Ed

After seeing all the mainstream media and schools sending information home about this MOMO thing, aspects of it didn’t ring true for me – so I spent this morning researching into it to try to get some more facts and details. My plan was to send this through to some of the local schools, but with local authorities and police supplying them with information, it’s difficult for them to consider the wider picture. As a result, I’m going to post it here on social media.

Please understand, I have no special skills here, I’m just one of many tech geeks that you all know – I’m no better than anyone else, but there’s an atmosphere of fear and scaremongering being spread about this MOMO challenge which is genuinely affecting our children and I wanted to try to make sure people around me know more of the facts and don’t distribute misinformation.

Fact

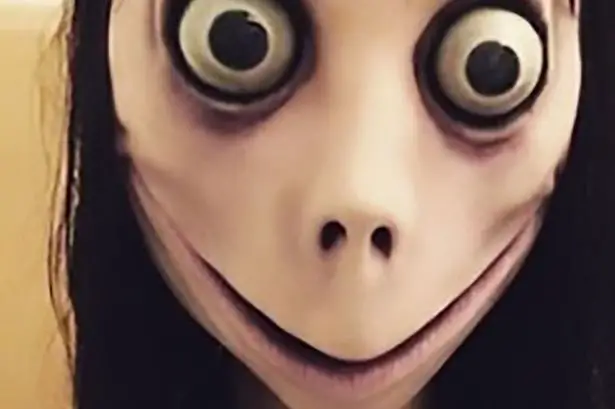

The “MOMO Challenge” was something that went around at least 4 years in one form or another although there is no evidence that it physically exists. The picture being linked with it is actually a sculpture called “Mother Bird” created by a Japanese special effects company in 2016 and features a face and breasts atop a pair of bird legs and has NOTHING to do with Momo.

The ‘MOMO’ challenge is credited as originating on Instagram in 2016 where ‘players’ of the game were invited to text a specific number and in return they would receive ‘challenges’ which inflicted pain or injury on themselves or others. That said, there’s no actual evidence of this other than lots of hearsay and viral misinformation. Think of it like “a friend of a friend knew a person who spoke to a person in the pub about this thing…”

There have been deaths because of it

This is entirely unsubstantiated. The death of a 12-year-old Argentinian girl which has been attributed to the Momo challenge is not entirely accurate and local authorities have confirmed that they are actually investigating an 18-year-old teenager who was believed to have met the girl before she hanged herself.

Additionally the tragic death of a 14-year-old girl by suicide in 2017 which has been attributed to Momo – when in fact, the girl appears to have had been found to be in possession of graphic images depicting self-harm and was entirely unrelated to this supposed ‘challenge’.

YouTube is being hacked

The reports that YouTube videos have been “hacked” is entirely false. It’s impossible to “hack” a YouTube video and YouTube spokesperson actually was interviewed yesterday (27th Feb) who has confirmed that “contrary to press reports, we’ve not received any evidence of videos promoting the MOMO challenge on YouTube. Any content like this is in violation of our policies and removed immediately”. Video “evidence” on other social media platforms purporting to show “hacked” videos have been either doctored to support their argument or created in response to the viral nature of this ’threat’ – they are not the root cause.

Why would they do this you ask? Money. YouTube has monetised its platform for years. By garnering more view and likes, you get a percentage of the advertising revenue from the ads surrounding your video. It’s a very lucrative industry these days and why there are so many vacuous YouTuber “celebrities” faking and fawning over random rubbish much to the delight of their (typically) young audience.

In addition to this, other kids games like Roblox and Minecraft are starting to appear in mainstream media now as sources of being ‘hacked’. This is not the case and is actually irresponsible (likely teenage or young adult) gamers creating skins and costumes ‘inspired’ by the publicity it’s receiving. In fact, Microsoft (who own Minecraft), have recently pulled the mod for the game which allow you to use the costume/skin in the game.

And so the cycle of misinformation continues.

But my child has a message from MOMO

No, they haven’t. What’s happened is that someone who’s been told about it is now using the scaremongering to further proliferate and add legitimacy to it. You’ve all been told about it from the schools and/or local authorities, you’ve spoken to your kids about it and guess what, kids are now talking about it.

It appears that my initial skepticism was indeed justified and it appears that the Momo challenge is nothing more than a virally-induced hype or a hoax than reality. The problem is that because of the misinformation from mainstream media and now being picked up by child organisations and police has further propagated, which is essentially more akin to an urban legend. This is a ghost story of the digital age.

The Momo challenge is being likened to (if you’re a child of the 80s/90s) will remember – the “Bloody Mary” or “Candyman” challenge, where you had to say it three times into a mirror and apparently they would appear (or something suitably more scary). The problem is that this story has been picked up through social media and completely over-inflated it turning it into “fact” (I heard it in the press, therefore it must be true).

A search through Twitter this morning for Momo is also highlighting the fact that the vast majority of kids had never heard anything of this challenge and as parents, we’re giving in to the fear and scaremongering by mainstream and social media inadvertently spreading and giving the story more validity.

Education and support needed

What this definitely has highlights is that the problem we have here is education and support – it’s just too easy these days to share, tweet, link without checking on validity. It’s why we now have the phrase ‘Fake News’ (Thanks Mr. Trump!). The dissemination of misinformation is just too easy and people share it based on scaremonging headlines and not researched facts. Educating not only parents, but children on social media and to dispel common misconceptions that have so that they understand more of what they’re doing. Understanding that snapchat pictures don’t ‘disappear’ after 10 seconds, showing parents how they can lock down and secure their facebook profiles and how to very simply research a headline for validity before sharing.

We absolutely have to be vigilant, but we also need to take responsibility for making sure that we’re not just spreading misinformation and fake news. As adults, we know of the distasteful underbelly of content online, but it’s not as easy as the mainstream and social media report it to be to “stumble” upon this content unless you specifically go looking for it.

Make a judgement call

What we need to do as parents is to be open with our children. Not only observing minimum age guidelines for social platforms, but making judgement calls as to whether your own children are emotionally able to comprehend accessing platforms which are designed for an older audience.

I don’t agree necessarily, for example, that YouTube has an age 13 rating. The reason YouTube (and other social media platforms) have a minimum 13 age restriction is actually nothing to do with security or content as is the common thought, it’s actually because they require specific personal information to register and under the US Federal Trade Commission COPPA (Children’s Online Private Protection Act), it’s a US Federal requirement that sites which ask for specific information not be used by people under the age of 13.

Prudent with access

The difficulty is that YouTube actually contains a huge wealth of educational content that children are missing out on. What we need to do is to be prudent with access and to educate ourselves to enable safe searching, create private profiles etc. Give them a safe environment and be open with them of the dangers, but to demonstrate the huge benefits they’ll get from using it.

I allow my children some relative freedom with their social media choices – you don’t need to be an expert in all of the platforms, just know what your children’s favourite platforms are and take an interest in them. Even set your own profile up and use them. You need to know how they work if you’re ever going to be able to protect your children online.

Condition of use

I also set a condition of use up front with all my children. Using the built-in software available on Apple devices, I’ve set up Family sharing, which means that all my children electronically ‘request’ to install apps and games. I then do some due diligence on apps they’ve requested and approve or decline the request, explaining to them the reason if I decline (maybe a security concern, content concerns, numerous bad reviews or just a badly conceived app). I regularly check their devices, with them sat next to me so that they can see that I’m not snooping and discuss anything with them that I might find.

But that’s just me, you can all come up with your own ideas of managing how/where/when your children access the Internet.