Jonathan Dodd‘s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

I’ve been helping to cut out things. I’m not too bad with a pair of scissors. Four years as a primary teacher made me quite a quick snipper, even though that was quite a while ago. Nowadays I just help with events at the library, although I do look longingly sometimes at things other people have made.

My attention is caught by photos or paintings or beautiful stitched things, and I watch the sublime skills of the musicians at the Isle of Wight Symphony Orchestra, or hear one of those perfect songs that sound so simple yet fill me up with meaning and emotion and memories. And I sigh, because I wonder if I’ll ever make anything as good or perfect as that.

A spliced creativity gene

To those of us who aren’t constant creators, the work that artists of all kinds produce appears to be magical. I feel this about so many things. I know the artists themselves never believe they’ve got it as exactly right as their imaginations first perceived it, but I can’t help thinking that they have a slice of genius in them, like a spliced creativity gene, to be able to think up these things in the first place.

I was looking at a beautiful art book the other day, and I was thinking about artists down the ages. It struck me that most artists were considerably less lucky in previous centuries than they are now. It used to be that rich people bought things, and artists of all kinds made their living not creating works and then selling them, but by begging for commissions and producing what the patron wanted.

Too many notes

Even when a true genius appeared, often their work had to be approved of by a rich person, otherwise commissions would dry up because they would go out of fashion. There’s a famous quote from the life of Mozart, when the success of his new opera was totally dependent on the approval of the Emperor. The look of sheer panic on Mozart’s face (in the film) when the only comment was – ‘Too many notes, Mozart!’ – was unforgettable, as was his anguished reply – ‘Which notes should I cut?’

I looked at all the classic paintings in the art book, and I couldn’t help noticing they all seemed to fall into three categories. The first was the ‘Look at me, how good I look with my lovely family and my rich clothes and my beautiful belongings. I can even afford the best artist for my portrait painting. The patron simply wanted to big himself up with the most chic and exclusive trappings. The painting was a good job, but was it what the artist actually wanted to paint? And was it actually Art?

A good seat in Heaven

The second kind of painting was the big religious work. ‘I’ve made my fortune. Now I need to show how powerful I am by spending a lot of money on a picture in the biggest church I can find, so everyone will see how important and generous I am. And at the same time those religious people tell me it’ll guarantee me a good seat in Heaven.’ Once again, it’s a good piece of work by the artist, and is rather good for his reputation as well, but would he have chosen to paint that? I rather think not.

The third kind of painting is usually some pastoral scene, or maybe something from Greek myths or early books in the Bible. It most often involves some completely gratuitous nudity and a lot of artistically-placed bits of diaphanous cloth or a handy tree branch, to hide whatever wasn’t allowed to be seen, at least in public. There could be only one reason for those commissions, and it had a lot to do with the lack of dodgy Internet sites in those days. Once again, I bet the artist would have wanted to paint other stuff.

The type of thing that would sell

So I started wondering if the artists in those days actually thought of themselves as superior workmen providing what the customer wanted, and either eking a living or growing rich on the proceeds. Or maybe they painted things they wanted to do on the side, but these were thrown out because they weren’t the type of thing that would sell. I actually don’t know that.

Nowadays, of course, things have changed enormously. Since money began to be spread around once industrialization and urban living became normal, and anyone was able to buy art if they wanted, a whole new culture grew up, where artists were able to paint what they wanted and sell it through agents in galleries. Some would still work on commissions, or found themselves reined in by the need to sell their work so they could eat, but for many this change opened up a whole new world of possibility.

Able to paint what they wanted

For maybe the first time ever, artists found themselves able to paint what they wanted. The tools of their trade became cheaper and better too. Portable easels and paints in tubes allowed then for the first time to paint anywhere, instead of making sketches and doing the painting in the studio. And anyone could get hold of paint and take up art as a hobby.

So art changed dramatically during the 19th century, in a way that rather shamed the formality and pretensions of the works of the previous centuries. It wasn’t just the Impressionists who changed the landscape of their world (literally), but in music and sculpture and writing and dance people were able much more to try out new things and methods, and there were buyers and consumers eager to watch or read or listen.

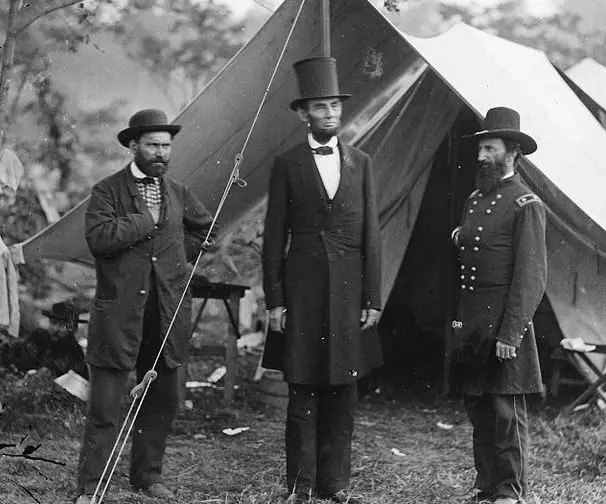

Familiar to everyone because of photographs

Entirely new art forms arose as well. Photography became enormously widespread, because anyone could have their photo taken, and they did. Politicians and famous people didn’t need to sit for their portraits so much any more. Abraham Lincoln and Queen Victoria and so many others started to become familiar to everyone because of photographs.

Then moving pictures were invented, and the joy with which the first film directors took to the medium and invented ways to use it for effects and never-before seen images was wonderful. And on and on it has gone, with television and the Internet and everything else.

The nature of art itself

But I still don’t know how much of this avalanche of energy and creativity is actually art. Perhaps that’s the whole point. Art used to be defined by people who judged new works and who were believed. Our museums and big prestigious art galleries are crammed full of beautifully-executed commissioned works that were far more about prestige and social standing than about the nature of art itself.

I suspect they’re there mainly because the artist was able to demonstrate extraordinary skill and technique despite, rather than because of the subject itself. What music would Mozart have been writing and playing if he had been born thirty years ago? Of course that’s an impossible question. Would his music be better than the music he wrote then? Also impossible. And I wonder whether we would have even heard of him had he been born in a farming family or a woodworker’s hut.

Anyone can create whatever they want

I like the idea that art has no boundaries or definitions any more. I like being able to dislike or love things that I see or hear or read, on their own merits and according to my own standards. I really like the idea that anyone can create whatever they want, whether they consider it to be art or not. I’ve even been able to buy modestly-priced works for myself to put on my walls, because I love them.

I have recently realized that I don’t have to be jealous of all those artists out there, because I am actually an artist myself. This is my art. You’re reading it! Although, of course, you don’t have to agree that it’s art at all.

If you have been, thank you for reading this. Any commissions would be gratefully considered…

Image: Huskyunder CC BY 2.0

Image: Thebrid under CC BY 2.0

Image: Herry Lawford under CC BY 2.0

Image: DcoetzeeBot under CC BY 2.0

Image: Tomwsulcer under CC BY 2.0

Image: hohum under CC BY 2.0

Image: Alexander Gardner under CC BY 2.0

Image: Slick-o-bot under CC BY 2.0

Image: © Jonathan Dodd