Jonathan Dodd’s latest column. Guest opinion articles do not necessarily reflect the views of the publication. Ed

There are moments in History where you can almost feel the ground of previous certainty shiver and shift below your feet. I often think of our existence as a species here on this planet in a similar way to the tectonic plates on which we stand. That ground feels really hard and solid, and for our purposes – e.g. existence, it works very well, mostly.

At the same time, those tectonic plates are grinding themselves against each other. The results are mountain ranges where they’re squeezed together, and earthquakes and volcanoes where they scrape each other, and occasionally great cracks where they separate. All this is measured on a timescale whose nuances we can’t detect, because individually our lives are short, compared to those of continents and oceans.

A large drop of soup in space

I imagine our planet to be like a large drop of soup in space, where it would form a sphere rather than a drop, as it would if subject to gravity. This sphere forms a thin skin all over the surface, just as creamy soup can, except it’s spherical. The magma, the incredibly hot molten rock that comes out of volcanoes, is the soup. We stir our soup with a spoon, and the skin gets crinkled and broken occasionally, and if it’s left alone, it reforms. There are currents in that magma, and the forces that act on our planet work like that spoon.

![]()

That’s our planet. That skin is what we call solid earth. Water collects in the crinkles, the soil and sand come from the wear and tear of the skin and debris arriving from outside. And crawling over all that are the assorted multitudes of lifeforms, of which the most intelligent, but not necessarily the most sensible, is us, the human beings.

We’re attracted to things that appear to be solid

Some people don’t like to think about that, because the whole thing seems rather flimsy and rickety. We’re attracted to things that appear to be solid, and we boast about making things that will be secure, and last for an extremely long time, and we cling on to tradition, because it masks the knowledge of the fragility of life. We might take delight in the extent of our knowledge and understanding, or we might seek refuge in the sonorous voices of those promising eternal life or the close attention of a deity who will keep us safe.

In the face of all this, some of us get impatient. Why, given the fragility of it all anyway, should we care about the past or the future? Why not just have fun and enjoy what we can grab while it’s still available? And some get angry because others appear to be leading golden lives, rich beyond the dreams of others, filled with privilege and apparent smugness and apparent lack of care or interest in those further down the pecking order.

We carry on struggling humanfully

But for most of us, it doesn’t matter whether life is fragile or not. We have jobs to do, and things to learn, and we need to cook and clean and protect ourselves and our children. For the most part, we’re impelled to make lives for ourselves, and usually these lives become ever more complex, and once we’ve started out, we need to spend more and more time keeping everything running. Some of us are good at this, some of us know we don’t quite manage, but we carry on struggling humanfully, and some fall by the wayside, with or without help and support.

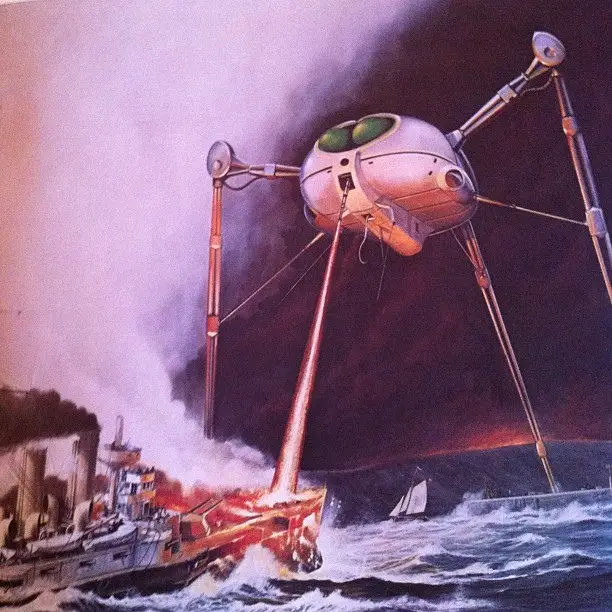

I’m sure that some alien scouting mission might see great similarities between us and those ant colonies we study, or try to repel from our houses. If they were able to look closer they would be able to see that we’re not the same as ants. Regimes that have tried to formularise human activity through economic or mechanical principles have all foundered so far, because we’re all far more than the sum or our parts, both individually and as a species. We’re ferocious in our endeavours, capable of extraordinary achievements and dreadful destruction and carnage.

Most of us do try to work together

The trouble with us humans is rooted in the same place as our greatness. We’re capable of opinions, but we can’t agree. If only we could all work together, or just not interfere with each other, everything would be so much better. At least that’s what we think. And most of us do try to work together. We obey the rules of the road, we support the teachers in our schools, and pay our taxes in exchange for the NHS and the Police. We feel bad about a lot of things, but we usually feel helpless to do anything about any of them.

And yet, we’re not always rewarded properly for all our efforts. People die. Mistakes are made, we fail to manage equipment or spend enough on social care, or we help our factory workers by doing deals with bad regimes elsewhere. We can’t grasp the full extent of the suffering of others far away, and we don’t understand how they can come to hate us. We feel affronted about that.

Civilisations strangle themselves before they fall

How on earth can we find a way to make all this work better? Part of it lies in the sheer complexity of it all. We set up systems, and we constantly tinker with them until they collapse from the weight of their own circuitry. We invent marvellous machines and gadgets that offer us freedom, but then so many of us take them up that we have to regulate all the fun out of using them. We manage to get better and better at combating disease and disability, but every new treatment or cure seems to cost more than before, and we end up worrying all the time about using up resources and juggling budgets.

There’s a certain logic to the idea that civilisations strangle themselves before they fall. Machines and buildings aren’t the only things that wear out and become too expensive to repair. Sometimes we argue about the value and cost of repairing something that’s probably no longer fit for purpose, rather than starting afresh. There’s usually justice in both points of view. At its extreme, there are some who see the whole of our civilisation as being rotten to the core, and needing to be completely torn down.

We don’t see ourselves as being one species

I have to admit to a certain amount of sympathy for this anger if you have been completely failed by the system. I feel guilty and somewhat sympathetic when they blame and punish the wrong people for their misery, or when their lack of education has been exploited by people seeking to manipulate them through misinformation and lies. I find it harder to think non-judgmentally about those who work to bring the system down when they have been beneficiaries of it.

But at the end of the day, the main difference between us and the ants is that we don’t see ourselves as being one species. For better or worse, we’re tribal. We gravitate towards others who resemble us, and we don’t generally react well to difference. I’ve heard it said that the only thing that could unite us would be a threat to our continuing existence.

There may be a way of doing our best better

Those of us who don’t argue against climate change may agree that we’re manufacturing that very threat to our continuing existence simply by ruining the planet’s fragile skin on which we live and depend. We don’t know how we might manage to reverse that trend. Or we may be clever enough to science our way out of it. But even if we do, there will always be something else to come along and challenge us.

I’ve got no answers to all this. And we haven’t reached the end of our story yet. There are themes and storylines still to play out. We don’t know where we’re headed or what’s going to happen. The story is the story, in all its messy gore and glory. We do the best we can. But there may be a way of doing our best better. We need to keep looking for those opportunities.

If you have been, thank you for reading this.

Image: Einladung zum Essen under CC BY 2.0

Image: maxpixel under CC BY 2.0

Image: George Hodan under CC BY 2.0

Image: Chris 73 under CC BY 2.0

Image: AlanMc under CC BY 2.0

Image: Christine Matthews under CC BY 2.0

Image: wapster under CC BY 2.0

Image: National Archives and Records Administration under CC BY 2.0